"A mahogany cabinet that doesn't smell of wax is like a beautiful woman they've cut a leg off. Something is missing. And modern man doesn't always remember what missing but that something is missing, you can feel it in your water, or how do you say... Do you want another beer?"

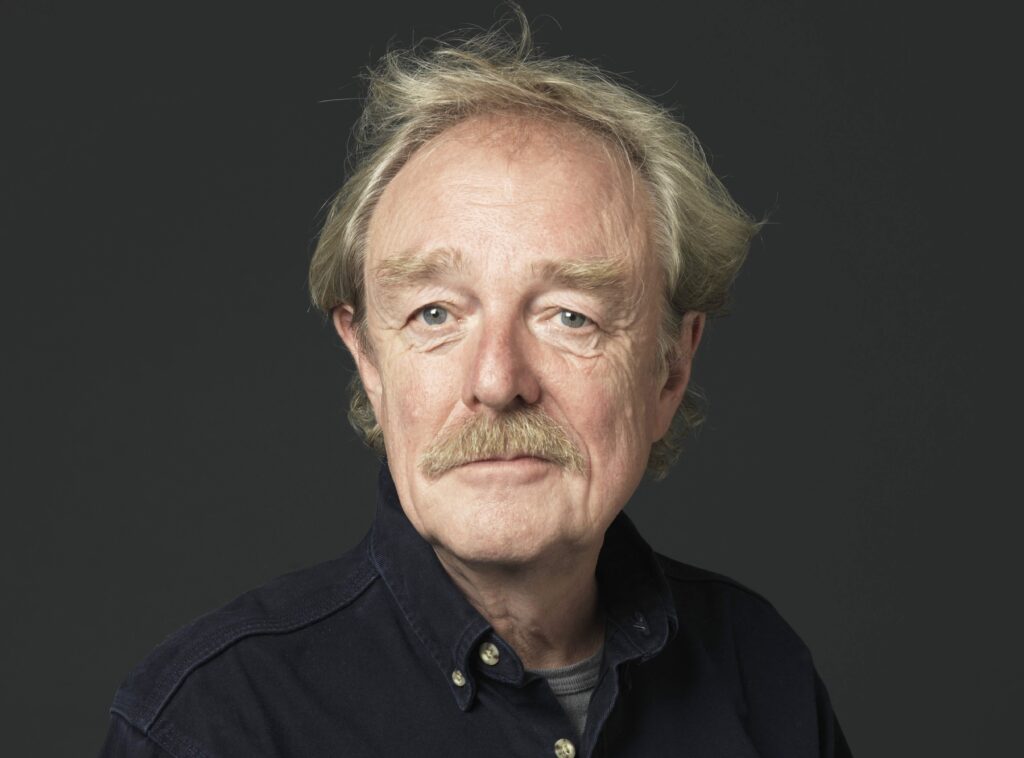

Text: Hans van Wetering Photography: A. Louwes, Corné van der Stelt

It is five o'clock, a Thursday afternoon in early November. In the study of Midas Dekkers In Weesp, dusk has set in.

Dekkers (Haarlem, 1946), Holland's best-known biologist, a contrarian figure with a penchant for subjects others would rather stay away from -he has written books on bestiality, on defecation, on the variation in human races- has just given a speech on the human senses, on the experience of beauty and that it has deteriorated since we exchanged our nose for our eyes as the most important sense in the course of evolution.

We so needed to live in the trees and trade our noses for those stupid eyes

Once upon a time, we started living in trees as monkeys, Dekkers teaches. And because, when swinging back and forth between branches, it is handy to be able to see ahead, our eyes moved from the side of our head to the front. But that was at the expense of our nose, there was no more room for it. So it became very small and doesn't do much anymore, which is unfortunate. Dekkers: "Your eyes first have to catch light and convert it into stimuli. Those stimuli then go to the brain and then you might see something.

But the nose is a direct link to that brain, that information comes in wham, directly into the brain. Smell is a superior sense, every sensible animal looks with its nose. We so had to live in the trees and trade our nose for those stupid eyes. And damn, being the only monkey like that we came back down, but we never got that nose back."

Not good news for our beauty experience, says Dekkers: "In the days when we still had a full olfactory system, we perhaps experienced more beauty pleasure than we do now."

Experiencing beauty is generally associated with looking, with hearing, with feeling if need be, but with smell?

"Charles Darwin," says Dekkers.

Darwin, that name will keep coming back, you have before Darwin and after Darwin.

"Darwin came out in late 19e century to his surprise to find out that beauty is not a veneer at all, as was generally assumed, not a sheen around something, but that beauty is in many cases the essence of life and without beauty you still run into very big problems."

Darwin discovered in late 19e century also that, to explain animal behaviour, to explain mating behaviour and mate choice too, you had to assume that animals possess a sense of beauty and that, unlike in humans, that experience of beauty in most mammals therefore goes through the nose.

Dekkers pours once more. A beer for the guest, the biologist himself sticks to gin ("The cheapest. For me, it's exclusively about the effect. If you care about the taste, I must strongly advise against drinking gin").

Back to the nose.

"If I went for a walk with my dog, which God forbid," (Dekkers is of cats) "I would see all nice things on the street. Then I would see beautiful women walking, and would I like cars then I would see beautiful cars driving. But that dog who is absolutely not interested in what I see. That dog is not propelled by the beauty impulses I get. That dog depends entirely on its nose. So it sniffs all sorts of things, and we don't understand why it sniffs this lamppost and not that one. And then we make up all kinds of stories about it, like: yes, that's because they give sexual signals.

But what we forget is that when smelling particularly nice smells, that dog must have the same beauty experience as we do. That dog doesn't think: gosh what an interesting smell this is, that might come from a very interesting bitch. No, that dog that thinks: this is the most beautiful smell I have ever smelt in my slow life."

How do you know you can call a dog's experience beauty?

"Well, or we term what we call beauty in terms that a dog would use for its sensation when smelling special scents or we term what that dog experiences in our human terms by calling it beauty: that's whatever. What matters is that that dog is not having a rational experience, like: what I smell are the traces of a bitch with whom, if she wanted to, I could experience very interesting things. No, just like us... when I, as a male, more or less heterosexual, see a beautiful woman, I first of all get a feeling and that feeling we then, because we mainly look with our eyes, refer to as beauty."

Beauty is ultimately a 'feeling', that's the bottom line. Animals have it as much as humans do. And, too bad for us humans, who have to make do with the eyes: the nose is a superior tool in this respect.

The nose that also immediately goes to work as soon as a visitor steps into Dekkers' house. The stately house, as Dekkers occupies the former town hall of the long-defunct municipality of Weesperkarspel. His study was once the council chamber ("Look, that big door was for the mayor and the little door over there for the public").

Modern architects are the most terrible people in existence

"Polishing wax," says Dekkers. "You're supposed to wax the place regularly. That's also what you smell when you enter the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna, for example: that wonderful smell of centuries of wax, of marble and stuffed animals and books. It is that same insane feeling of happiness that comes over you when you enter an old bookshop or old library. That you don't just see mahogany sees, but that you also smells, that you have the experience, That you have a Totalerlebung have."

Overall experience, it is a concept that keeps recurring. Asked to point out something in his study that represents beauty to him, Dekkers falls silent. The room is full of extraordinary objects -vitrines with stuffed birds, fossils and skulls, antique viewers and stamps, countless jars of ink and pens, old books and manuscripts, antique typewriters- but Dekkers says he cannot name a single object, not want call it, because that misses what for him is the essence of beauty: that total experience.

It is his study as a whole, that combination of objects, the harmony between them. Also that smell plays a role in that perception. And the way the space sounds. "The pleasure that enters through the eyes, we know as beauty. But there is also such a thing as the experience of all those senses together, and there is no word for that. When those sense impressions together form a harmonious whole: you would actually have to invent a new word for that."

It is his study as a whole, that combination of objects, the harmony between them. Also that smell plays a role in that perception. And the way the space sounds. "The pleasure that enters through the eyes, we know as beauty. But there is also such a thing as the experience of all those senses together, and there is no word for that. When those sense impressions together form a harmonious whole: you would actually have to invent a new word for that."

Dekkers disappears downstairs once more. Creaking steps. Somewhere a heavy door closes with a dull bang. Outside, it has gone dark. The streetlights cast their yellowish light on the wet rained pavement.

"Modern architects are the most terrible people around," says Dekkers when he is back and ("you don't have to leave yet, do you?") downs another beer. They design a house on a computer screen, purely by eye. But is there anything nice to smell in modern houses? No! Is there anything nice to feel? No! Is there anything nice to taste? No! And the acoustics are really terrible too!"

Dekkers is a tireless orator. It comes to experience beauty in nature ("They say tastes differ, but I have never heard anyone complain about nature, like: today nature is very ugly, or: this elephant has turned very grey"). It comes on joggers ("It doesn't look like it, and why not? We are not built for it. Whereas a flying bird, it is always beautiful, because it is doing something it is meant to do: beauty is perhaps also the feeling you get when something is biologically right").

It comes, finally, to 'impermanence'. In 1997, he published a book with that title. He calls it an ode to the beauty of decay, an ode and an indictment all in one. "Decay is inseparable from life: things are born, reach a peak, and then decay. But these days, when something passes its peak, it is immediately replaced. Things are not given time to complete their cycle, while therein lies beauty: that you see the whole cycle. Like a human life is beautiful when first you are a baby, and then you make a career, and then you become a nice sweet old man with no teeth sitting in front of his cottage. And then if it's also a nice funeral, yes, it's been a nice life."

It's not about everything having to collapse, Dekkers clarifies: "It has to be that everything happens at the same time: part is born, part is at its peak, and part is in decline. But we don't want to see the latter anymore."

He tells of a villa on the outskirts of Weesp, Villa Casparus, built in the late nineteenth century for the owner of the Van Houten cocoa factory. "When Van Houten went under, that villa started to decay nicely. At the back was a kind of moped factory, it was a secretive place, a favourite spot. A property developer has now turned it into expensive flats and built two hideous Soestdijk-like wings against it. It no longer has any grandeur, nothing mysterious. It would have been better off slowly decaying, with that moped man still fiddling around there. A beautiful ruin it could have become. That would have been the most beautiful thing. There should be such places in every full-fledged city."

A silence falls.

"Everything is getting uglier," says Dekkers: "Was once on a poster by Loesje. If I made a poster myself now, it would say 'everything is getting uglier'... You understand: biologist, old, not someone prone to cheerfulness anyway."

Pret eyes.

"I've written fifty books, spent a lifetime trying my best to get it a little bit in the right direction and, you may say that at 78e than say, I failed. A while ago, I decided enough was enough, which felt like a liberation. The writing itself I find terrible. But then I found out that no book writing is even worse. Now I've been at it for a year. What it's about? I'll give you one more beer first and then I'll reveal it."

"The human deficit," he says, once back.

Pret eyes again.

"But yes, now I have saddled myself with having to make it real. Not a book to write at eighteen no. Whether it's a book to write at 78, that too remains to be seen."