"Actually, I would have preferred to be at home right now, with my family," says Jussi Adler-Olsen (b. 1950) as he looks outside, where cyclists on the Herengracht are already cursing as they swerve for a van parked in the middle of the road...

Text: Hans van Wetering

The interview takes place not long after Russia invaded Ukraine. Adler-Olsen is in Amsterdam to promote his latest thriller, Sodium chloride, volume 9 in his so-called Q series around inspector Carl Mørks (and the Q police department in Copenhagen) and the 2013 film adaptation of The Marco Effect. Since the first part of the series was published in 2007, it has sold 27 million books worldwide, one million of them in the Netherlands.

In the now

But the war in Ukraine is inescapable. Stories of atrocities and war crimes dominate the news. The world is suddenly a different one and that affects his work, says Adler-Olsen. "My books evolve with the times. I am forced to think about that world, and that is reflected in my books. Those books play in the here and now, follow each other directly in time. Sodium chloride ends on Boxing Day 2020. And actually, the new book I am going to write, volume 10 of the series, should continue right after that, on 1 January 2021. But I hesitate, maybe I should skip a year and go straight to the present tense. I can't ignore the terrible things going on right now."

Abuse of power is omnipresent in Adler-Olsen's books. Abuse of power in society, abuse of power in families. It has to do with his background, says the author. He studied psychology and political science. And then there is something else entirely that makes Adler-Olsen almost the perfect 'education' for a thriller writer.

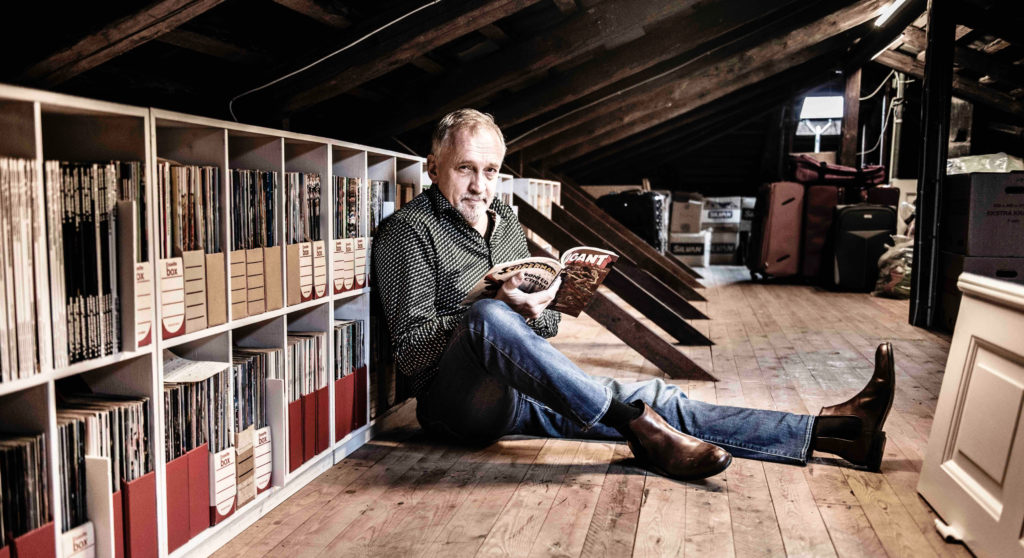

Photo: Politikens Forlag

Electroshock and worse

"I grew up in a mental institution. My father was a psychiatrist and in those days it was common for families of employees to live in the institute itself. We also ate together, in a communal kitchen, with the nurses, with doctors. It was the early 1950s; psychopharmaceuticals didn't exist yet, you couldn't really do anything. Treatment was terrible: patients were tied up, given electroshocks and worse. Some were in cages, virtually without clothes. My father was a good man, but I was scared to death of some of the other doctors. Those really behaved like kings, real goons. One of the doctors used to take a glass of water at dinner, put two raw eggs in it and then drink it in one gulp. That was really an incredible bastard. Lobotomy was his speciality."

It was the world upside down. A world where patients were victims and doctors were the real villains, where children interacted with patients on a daily basis, something Adler-Olsen's father believed was good for both.

"I had a bodyguard, a ship captain with a pockmarked face. He was a huge guy who always wore one of those enormously wide John Wayne belts and the story went that he could kill someone with one blow: it's one of the few really existing people I've used in my books, in Alphabet House. But he was not needed at all, it was not dangerous."

Befriended killer

The author even built a friendship with some patients. "Inspector Carl Mørck is partly based on one of those patients. He had killed his wife, but to me he was a nice man. He often cried, and then I comforted him. It taught me early on that good and evil are not absolutely separate, that both can dwell in one person. Later I understood that it can actually happen in any head. You see that again now in Ukraine."

Badness is often associated with a conscious action, says Adler-Olsen, but it is just as often an absence of consciousness, absence of empathy. The latter, according to the writer, is an essential characteristic of our times, where it is always about the 'I'. His new thriller, Sodium chloride, is about people who have no interest whatsoever in what they bring about, who do not empathise with the other person in any way.

The latter is exactly what Adler-Olsen does always do extensively before writing a thriller: "I know the characters in my book long before I write the book. I really immerse myself in those characters, try to get to know them. For the Alphabet House (his first thriller, from 1997), I first wrote eighty pages about the childhood of main characters, two pilots, but you won't find any of that in the book. I didn't use those pages. The book starts on page 81, so to speak, but I needed that youth to understand the characters, to understand why they spoke the way they spoke, said what they said."

The latter is exactly what Adler-Olsen does always do extensively before writing a thriller: "I know the characters in my book long before I write the book. I really immerse myself in those characters, try to get to know them. For the Alphabet House (his first thriller, from 1997), I first wrote eighty pages about the childhood of main characters, two pilots, but you won't find any of that in the book. I didn't use those pages. The book starts on page 81, so to speak, but I needed that youth to understand the characters, to understand why they spoke the way they spoke, said what they said."

Selfish world

It is what the author also did for the Q series. But over the 15 years the series has now been running, the main characters have evolved, Adler-Olsen says, as the society we live in, and in which they live, has also changed, become more selfish.

Outside, people are honking. The van is still standing where it is. An impatient taxi driver hangs out of his car. Then the driver of the van approaches. The taxi driver raises his hands to heaven, visibly irritated. The driver smiles slightly, shrugs his shoulders, gets in and drives away calmly.

He hopes his books cause readers to think about the society in which his thrillers are set, Adler-Olsen said a little later. "My books always have a message. Why else would you write a book at all?"

The main character of The Marco effect, part 5 of the Q series whose recent film adaptation is now available to watch on streaming platform myLum, is about a gypsy boy - "and actually he is not even that, because he has no background at all"- who gets into big trouble. The underlying message of the film according to the writer: "Take care of your children, impress upon them that there are other children living in much worse conditions, make them look that way from time to time."

However, Adler-Olsen does not believe that the social criticism in his books really makes a big impact. A thriller does not, because (laughing): "In Volume 7, Selfies, which appeared in 2016, I wrote about the effect of smartphones. Well, that didn't really help either."