"I am not a car repairer," says Farid Kazem. "It's not a matter of denting, spraying and the next please, I'm dealing with people."

Text: Hans van Wetering

A business park under the smoke of Schiphol Airport, a sunny morning in May. Farid Kazem (London 1959), the 'plastic surgeon to celebrities', as he is known, has just delivered a long, critical speech about the modern, hurried world, in which people want more and more, more money, more travel, further and further.

"What is beauty?" was the question it started with. "Balance between inner and outer," Kazem had replied, and that you can see beauty in everything, if you look closely, even in chaos. After which corona time came up: that we were suddenly forced to stand still and look inward, our individualism giving way for a moment to the understanding that we need each other. In his own words: "Finding the beauty in the realisation that you can also be happy with simple things, with the fact that you have each other, that we sit together, that we have a roof over our heads, that we have food. Those simple things: that is also beauty."

Beauty is not limited to aesthetics, it comes down to that. The motto also applies to Kazem's own practice, he says. "If you are unhappy, you can have all sorts of things done to yourself, but you are still unhappy. It's about balance, about inner-external."

It is somewhat confusing: I am sitting opposite a plastic surgeon, and it is mostly about the inner self, about happiness, about love. It is as if, looking for Kazem the plastic surgeon, I have stepped into a wrong door.

Kazem has to laugh. About his profession, aesthetic surgery (plastic surgery is broader, includes reconstructive surgery), there are simply a lot of prejudices, he responds. "There are of course colleagues who say: the customer is king, if the customer wants something, I will do it. I see it differently. Sometimes I refuse people. Then I try to give insight as to where the underlying problem lies, recommend a conversation with a psychologist or a coach."

"With some people, full lips don't fit at all," he says.

Moreover, a 'you ask, we turn' approach can work like a boomerang, says Kazem. "If you wield the knife too easily, if you don't listen carefully to the underlying demand and desire, you run the risk that the customer will still not be satisfied afterwards, even if the operation is technically successful."

Kazem is called away. A quick look around. A dark wood cabinetry, a few office plants, sleek furnishings, the whole thing oozes luxury. Everything is right. Except for a reproduction of Paul Gauguin, which stands somewhat forlornly against the wall in the corner, behind a flipchart, waiting for someone to hang it on the wall. On a cabinet is a Mac computer of an unknown model.

"That's the Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh," Kazem says when he gets back. "Only 12 thousand of those were made, a wondrous machine, with a TV tuner too. In the mid-1990s, when it came out, it was state-of-the-art. And the peculiar thing is that it still looks modern."

"That's the Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh," Kazem says when he gets back. "Only 12 thousand of those were made, a wondrous machine, with a TV tuner too. In the mid-1990s, when it came out, it was state-of-the-art. And the peculiar thing is that it still looks modern."

It is a small step from the Macintosh to the concept of 'classic beauty'. Kazem hesitates, "I don't know if that exists, beauty is time-bound. In the 1980s and 1990s, everything had to be slim, size zero. Now we are moving more towards curves again. It's a wave motion. Marylin Monroe was the ultimate sex symbol in her time, but when I look at the pictures I see a chubby woman. I like that myself, but it's not a classic shape, you wouldn't put her on the catwalk now."

What about faces, you do have classic beauty there, don't you? "Sophia Loren," Kazem replies immediately. "Claudia Cardinale, Monica Belucci. Women with charisma, with power. If you Sophia Loren compares with Marlin Monroe then Monroe is a peasant girl and Loren is a princess."

Even ugly people can be attractive, according to Kazem, "Mick Jagger for example. The proportions are wrong: skinny guy, way too big lips. But somehow he is attractive, had the most beautiful girlfriends, and not just because he was rich and famous. It has to do with dynamism, with charm."

A gold Maneki neko, a Japanese 'lucky cat'. Kitsch, and in itself nothing beautiful about it, ugly actually. Still, the promise of happiness, however irrational, can make you look at it differently, Kazem says. Yes, even that you perceive a certain beauty in it as a result.

A gold Maneki neko, a Japanese 'lucky cat'. Kitsch, and in itself nothing beautiful about it, ugly actually. Still, the promise of happiness, however irrational, can make you look at it differently, Kazem says. Yes, even that you perceive a certain beauty in it as a result.

"Sometimes I refuse people, recommending a conversation with a psychologist or a coach."

Aesthetic surgery is a growth market. Research suggests that the industry could easily grow by 300 per cent in the Netherlands over the next five years. The taboo still attached to it in the Netherlands - you are easily called "superficial", "fake" - is diminishing, but it has certainly not disappeared yet. "People who have had something done rarely talk about it, out of shame, for fear of being condemned. So clients also don't pass on how well they were helped.

Word of mouth hardly exists in the world of aesthetic surgery," Kazem says. "Not in the Netherlands. I know women who don't tell their husbands because they have the prejudice that it makes you look fake. plastic fantastic. While they therefore don't realise that their wife has been coming to me for 15 years. I often hear: I can see from a kilometre away whether someone is botoxed or not. Then I say: no, you can't see that at all. What you see are the excesses, how the not must."

The growth is not only due to the (slow) disappearance of that taboo. It also has to do with more and more men taking the plunge: "Twenty years ago, 99 per cent were women, and the one per cent men were mostly gay. Now the ratio is 80/20, and straight men are coming too". This is also due to technological advances in the profession. Because of the shift from invasive to non-invasive treatment ("Fifteen years back, 80 per cent of what I did was surgical, now 20 per cent").

Men don't want surgery, Kazem says, don't want to be out of the running for a long time. And new techniques, such as coolsculpting, a non-invasive way to remove fat, and emsculpting, for strengthening your core ("One session with emsculpt is like doing 20,000 crunches"), now make that possible.

"You're 50, why do you have to look like 20?"

The growth can also be traced to the fact that people are starting it earlier, to 'accompany' ageing processes, Kazem says. And because of the advent of social media: you used to look in the mirror a few times a day, now you see yourself constantly on your mobile phone, via selfies. And what you are also constantly presented with on Instagram and related media: retouched selfies of peers. It makes young people insecure, Kazem thinks, that they really want to become like those 'perfect' others.

"It has gone overboard, people are now really looking at a microscopic level: every little line, every little thing has to be corrected. And that makes you almost get a kind of cloning: I see far too many people who look very much alike. Young women with Russian lips: a professional looks at character, then looks at what fits that face. For some people, full lips don't fit at all. Then you just have to say: don't do it! And if you do that year in, year out, things get stretched. And what if, ten years from now, full lips are no longer in fashion? Then you have to have surgery to tighten it again, resulting in facial scarring."

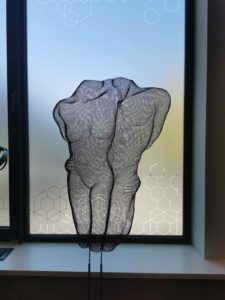

By the window is a mesh sculpture, Randy Cooper is the artist's name. A man and a woman intimately entwined. What is striking: the washboard that is nowadays considered the ideal of beauty is emphatically absent. Man and woman have curves, fat on their bones.

By the window is a mesh sculpture, Randy Cooper is the artist's name. A man and a woman intimately entwined. What is striking: the washboard that is nowadays considered the ideal of beauty is emphatically absent. Man and woman have curves, fat on their bones.

"You should not want to meet demands that are not realistic," Kazem says. "The same goes for age. I sometimes say to people: you're 50, why do you have to look like 20? Every age has its charm. That doesn't mean you should just let everything go to waste, but it's okay to be a bit heavier at 50 than when you were 20. Then, of course, you can go to the gym like crazy and starve yourself, but I find that a bit pathetic. It's about balance, inner and outer, that's what it comes down to again and again."