He designed the most beautiful cars ever made. The Ferrari Daytona? It was his pencil that drew the lines. The Ferrari 250 LM Speciale and the Ferrari 308 GTB/GTS? They sprung from his brain. Pininfarina designer Leonardo Fioravanti on a life of beauty.

Text: Hans van Wetering Photos and illustrations: Leonardo Fioravanti

Leonardo Fioravanti (not to be confused with the surfer of the same name) is, despite his 83 years, a busy man, always on the go. He is very briefly back in Milan, the city where he spent a lifetime working and still lives, when he speaks to GW.

"With that problem I have been dealing with my whole life," says Fioravanti and starts laughing. "Beauty has always fascinated me, I fought with it. During my studies, I came across Plato. His definition was: 'Beauty is the brilliance of truth'. For me, truth is directly linked to functionality. Every product I have ever made has been designed from function. That function then becomes visible in the aesthetics: when you see a wheel, you see, as it were, an explanation of what the thing is for. Finally, people interpret that aesthetic with their 'personal feelings': that is the style. So it's about function, aesthetics and style, in that order. You can make beautiful cars, create real beauty, but it all starts with function, with finding solutions to design challenges, for example in terms of the relationship between engine cooling and aerodynamics."

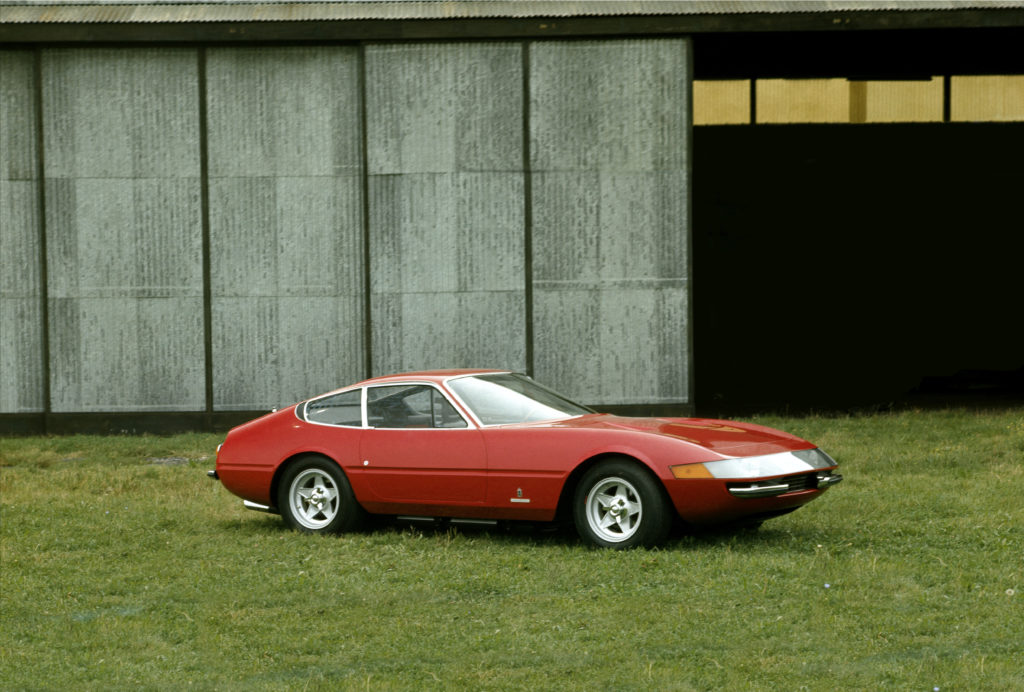

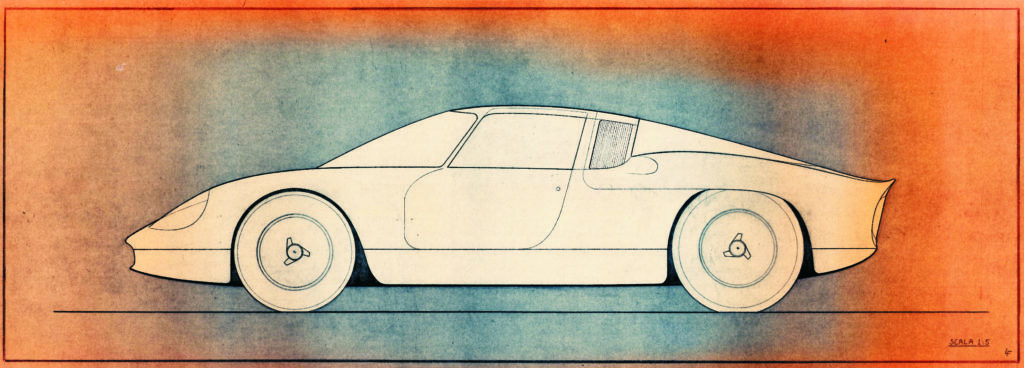

The designer seeks solutions and everything stems from the function of the thing. The hand carelessly sketching lines on the paper to 'create' a hair-raisingly beautiful bodywork from nothing is an enticingly romantic image. Reality is really different, says Fioravanti again. But then that 250 LM Speziale, to name but one, with those wondrous doors running into the roof and that rear end like a seemingly endless wave: does he really want to say that those shapes arose purely from functional considerations?

The designer seeks solutions and everything stems from the function of the thing. The hand carelessly sketching lines on the paper to 'create' a hair-raisingly beautiful bodywork from nothing is an enticingly romantic image. Reality is really different, says Fioravanti again. But then that 250 LM Speziale, to name but one, with those wondrous doors running into the roof and that rear end like a seemingly endless wave: does he really want to say that those shapes arose purely from functional considerations?

"The 250 was my first love, the first car I drew for Pininfarina. I had just left school. An American wanted a street version of the 250 Le Mans: the race car. All sorts of things had to be modified. That American was extremely long, so getting in proved very difficult. That's how that extra doorway in the roof came about. I didn't like the rear of the original version; I felt that the aerodynamics could be better, so I made the rear longer. That had a great effect. The street version turned out to be faster than the race car. It was the world's first supercar in 1965, a year before the Lamborghini Miura."

"The 250 was my first love, the first car I drew for Pininfarina. I had just left school. An American wanted a street version of the 250 Le Mans: the race car. All sorts of things had to be modified. That American was extremely long, so getting in proved very difficult. That's how that extra doorway in the roof came about. I didn't like the rear of the original version; I felt that the aerodynamics could be better, so I made the rear longer. That had a great effect. The street version turned out to be faster than the race car. It was the world's first supercar in 1965, a year before the Lamborghini Miura."

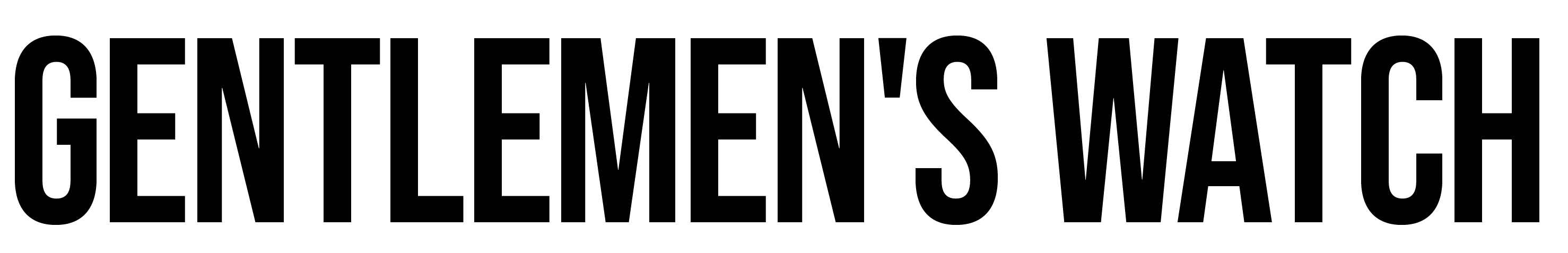

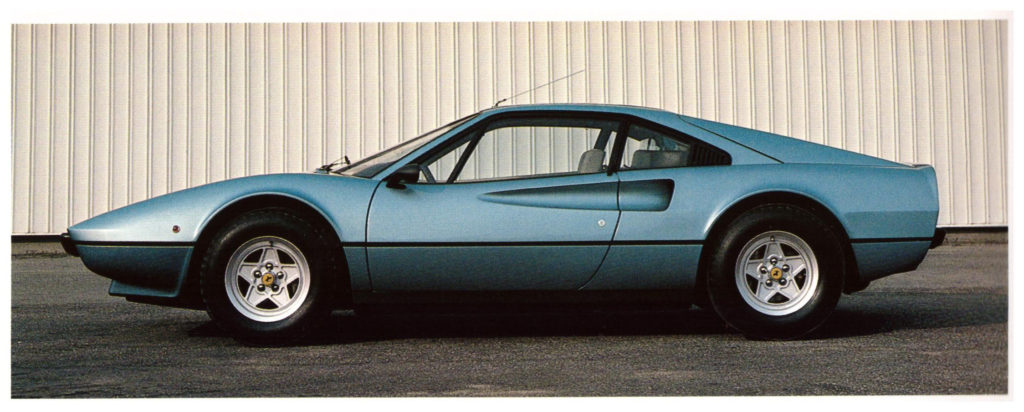

"And the car was also of great beauty," he then says carelessly, adding in the same breath, "but again: everything starts with function." He says it like a mantra. "Another example: the Ferrari Daytona. The function of a Ferrari is to win races, and the Daytona did that thanks to good aerodynamics, a great engine and good visibility. The 308 GTB, another design of mine, of all the Ferrari is the one that won the most rallies."

A Ferrari is first and foremost a racing machine, everything must serve that one purpose: to win races. Beauty is a by-product, that's the bottom line. So why those cars can still move grown men to tears, why many millions are laid down for cars he once designed, which will never race again in their lifetime and in 2020 are mere objects to look at, remains a bit of a mystery.

A Ferrari is first and foremost a racing machine, everything must serve that one purpose: to win races. Beauty is a by-product, that's the bottom line. So why those cars can still move grown men to tears, why many millions are laid down for cars he once designed, which will never race again in their lifetime and in 2020 are mere objects to look at, remains a bit of a mystery.

No art

What about those beautiful pencil drawings included in his autobiography, the ones he did as a youngster? Fioravanti laughs. "Do you like them? Ah yes, thank you." But no, so it all has nothing to do with art what he does. The idea that Michelangelo, had he lived in the 20th century, would have designed cars is also beyond Fioravanti: "Art is about beauty without any function, without restriction - "Please, don't confuse art with our work!"

The conversation turns to the phenomenon of aerodynamics, something that has occupied his life. "I really am a maniac when it comes to aerodynamics," says Fioravanti. "I was a racing driver myself before I joined Pininfarina, which is also why I got that first commission for the Ferrari 250 LM. I was already fascinated by speed as a child. And the streamline determines not only the energetic properties of the car, but also to a large extent the shape, so the beauty too."

No, it doesn't mean that only streamlined cars can be beautiful, says Fioravanti, "A city car doesn't have to be fast, the streamline doesn't matter much then. Much more important is good visibility. A city car should therefore be designed from the latter function. The Fiat Multipla, designed by the way by one of my former employees, was always scorned. But why should the Multipla be ugly? The design is functional: visibility is optimal, with that high seat and those large windows." The latter has to do with the low beltline, says Fioravanti. Cars these days almost all have a high beltline and therefore poor visibility. It is thought from the shape, and that annoys him. "Another thing: in the bottom of the front of almost all cars in the world there are three holes. The middle one is for cooling, but the two holes on the sides are fake, have no function." He laughs: "You understand it's not a good time for me."

Functionality again as the holy grail. It also returns when he answers the question of what are the cars he is most proud of. Fioravanti again mentions the 250LM (first supercar), the Daytona (designed as a race car and hugely successful in it) and the 308GTB (first Ferrari designed in such a way that large numbers of them could be produced). But his pride does not only apply to Ferraris.

Functionality again as the holy grail. It also returns when he answers the question of what are the cars he is most proud of. Fioravanti again mentions the 250LM (first supercar), the Daytona (designed as a race car and hugely successful in it) and the 308GTB (first Ferrari designed in such a way that large numbers of them could be produced). But his pride does not only apply to Ferraris.

New ideas

In 1994, the Fioravanti Sensiva was the first public prototype by Fioravanti SRL (the company he founded in 1987), and the world's first - picture-perfect - sports car with a hybrid drivetrain: sixteen years before Honda put the first hybrid sports car into production with the CR-Z. The Sensiva was full of new ideas. Serial batteries, now called range-extender, and a small fuel turbine to charge the batteries. Each wheel had its own electric motor, the high-tech tyres transmitted data to the system, and supplied energy to the system via friction. Electric sports cars of today - Porsche, McLaren - use Fioravanti patents. The 'Smart Tire' that Pirelli came up with two years ago: it is based on patents derived from the Sensiva.

"I see myself first and foremost as an engineer." So 'inventor' he could also have said, because over the course of his long career, Fioravanti developed countless new inventions. More than eighty patents were put into production, by car brands worldwide. "I want to invent new concepts," he says about this, "the Sensiva is a good example of that, improving what already exists has never interested me."

Fioravanti starts talking about the 2000 Fioravanti Tris, the number five in his series of favourite cars of his own. A remarkable choice, as Fioravanti left the design of the -not exactly dazzling- Tris to an employee. His pride applies to the concept. The Tris was all about production efficiency and cost savings. The car was built from recycled materials. The aim was also to reduce the number of parts as much as possible. "I asked myself: why is the door on the left side in cars always different from the door on the right? Why is the front bumper different from the rear bumper? Why are lights at the front different from the rear?" And so the hatchback got three identical doors and front and rear were identical.

From the Tris back to the magical marque from Maranello. Fioravanti also designed for Lancia and Alfa Romeo, among others, but Ferrari, he says, is of a different order: "Perfection does not exist in the world, but Ferrari sometimes comes close to it. It's about getting it right, getting it exactly right, no more and no less, no detail being superfluous. Then beauty can emerge. I say it again: beauty arises from truth. A true thing speaks for itself, and true beauty needs no explanation."

From the Tris back to the magical marque from Maranello. Fioravanti also designed for Lancia and Alfa Romeo, among others, but Ferrari, he says, is of a different order: "Perfection does not exist in the world, but Ferrari sometimes comes close to it. It's about getting it right, getting it exactly right, no more and no less, no detail being superfluous. Then beauty can emerge. I say it again: beauty arises from truth. A true thing speaks for itself, and true beauty needs no explanation."

But how beauty then arises exactly, is still sometimes elusive, says Fioravanti after some urging. "Design goes from function to aesthetics to style, but where exactly beauty arises in the transition between those stages is far from clear. Yes, in the end beauty is always also a mystery."