We are all digitally connected. And therefore digitally vulnerable. Today, highwaymen no longer lie behind the bushes, but hide behind tempting links that open wide the door to everything we hold dear....

Text: Hans van Wetering Portrait: Anke Meijer.

UPGRADE

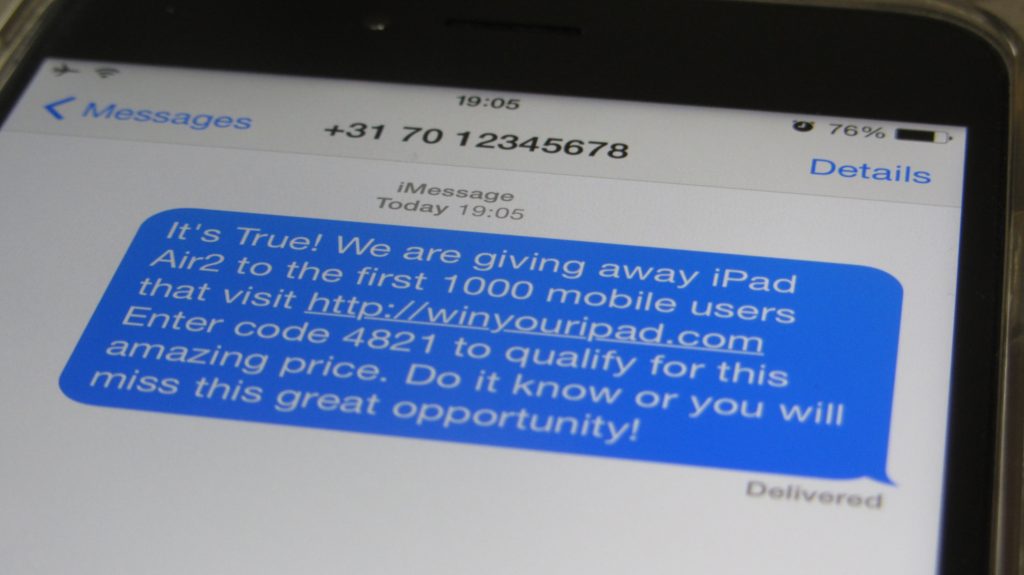

In the week leading up to the interview with journalist-writer Hans Klis following his Storytel Original podcast series Hacked! about notorious hacks and cybercrimes, I get a Whatsapp message. It's my daughter: "Hey dad, I have a new number, different provider, was much cheaper" (smiley, winking). And a little later: "I'm having a little urgent problem... I can't get into my online banking and I need to pay a bill... I wanted to ask if maybe you could advance it. As soon as I can get into it myself I'll get it back to you!" More smileys. Sensing wetness, I ask for grandma's first name. "What kind of weird question is that dad?" comes the response right away, "I'm already late in processing the bill!" It's a familiar scam. My daughter was in reality a shady figure who had somehow gotten hold of our data. The scariest part: it is real as my daughter writes. I know about the existence of the scam and yet, for a very brief moment, I am left wondering.

"Cybercrime is also often super personal," says Klis. "Ransomware and phishing are a huge problem. All those messages you send that you really don't want everyone to see, the photos of your children when they were young... They get access to all your life. That's why digital security has to be such an important issue."

"Cybercrime is also often super personal," says Klis. "Ransomware and phishing are a huge problem. All those messages you send that you really don't want everyone to see, the photos of your children when they were young... They get access to all your life. That's why digital security has to be such an important issue."

FLIGHT TICKET

Klis came into contact with the hacking world when he made a documentary on North Korea for BNN-VARA. While researching the funding flows behind the regime, they stumbled upon a huge cyber hacking operation. This ran via bitcoins and in the form of a digital heist on the Bank of Bangladesh, which attempted to rob the bank of a billion dollars.

"But it is a big misconception that it is mainly something that affects big companies and governments," says Klis. "We give away a lot of information. We should think better about our passwords, think better about what we share on social media, stop posting a picture of your plane ticket saying, "Hey, nice trip to New York!" And then having someone check in for you. Identity fraud is a danger. We have no idea how vulnerable we actually are, also because we know little about it." That has surprised him most during his research into cybercrime, Klis says, how ubiquitous it is in our lives and that we never actually think about it. "That it is so big and affects so much in the world."

And yes, he has become more careful himself. In front of his laptop's camera is a slider. He sometimes puts his phone away when discussing something sensitive, "because that's basically a listening device." That story is no urban legend. "Saudi dissidents around the world were found to be bugged via spyware on their phones," he says.

He himself has never been hacked, says Klis, "but I'd rather not say so, because then you'll just see that there are people who think: oh no? Then I'll give it a go anyway!" It doesn't mean he was never a victim of data theft. "I did find out that my personal data was leaked from seven very large data leaks. These include dates of birth, my email address, passwords I used with those services. So I changed all those. My credit card has also been used by other people at times."

You can easily check whether your own data has ever ended up in such an obscure database via the site www.haveibeenpwned.com. Enter mail address or mobile number and you'll see if it's wrong. My own mail address turns up in five databases. That probably explains the app from 'daughterlove'. My data ended up there thanks to hacks of Dropbox (in 2012) and LinkedIn (also 2012), among others, I see. The size of one of the databases is beyond comprehension: more than four billion user accounts of 1.2 billion unique individuals.

BLACK YOUNG

"At the same time, there is also a very professional side, involving serious criminals," says Klis. "The Carbanak gang I cover in the series worked with the Russian mafia, robbing ATMs. That involved more than a hundred banks, worldwide. Altogether a billion dollars."

Numerous governments and businesses have fallen victim to ransomware in recent years. During Corona, there were even attempts to extort hospitals this way. And then there is the fear of essential infrastructure being attacked. "You really don't want them to get into Borssele. Iranian hackers already penetrated dam systems in America. The NotPetya virus that hit Ukraine in 2017 shut down many power plants."

There is now much more awareness of the dangers, though, including among governments, says Klis. "One of the five stories in the podcast series is that of Diginotar: the Beverwijk-based company that gets hacked and suddenly causes people in Iran to think they are logging into their Gmail, but are actually bugged. The government had no idea what Diginotar was all about. That was a decade ago now. Now the government is emphatic about it, but digital security is insuring you for something that might happen in the future. And if, as a government, you then have to make cuts, meet policy goals, or meet your targets for a company, digital security is actually a block on your leg. You have to put a lot of money into it, and at the same time you never know if it's enough or too much."

It is an arms race, says Klis. That there is more awareness of the dangers is positive. But on the other hand, our society increasingly relies on a digital infrastructure, resulting in additional vulnerabilities. And technology is also developing faster and faster. "Ten or 20 years ago, programmes were updated once every few months to take out vulnerabilities. Now companies like Facebook are really constantly changing things, writing code, and then bugs naturally creep in."

GOOD HACKERS

Flaws that companies and governments then try to detect by hiring hackers of their own. There are also companies, such as Silicon Valley-based Dutch company HackerOne, where you can hire hackers to detect vulnerabilities in your own software. The so-called zero-days, vulnerabilities in new software that a developer is unaware of, that no one has yet armed themselves against. "For example, the Stuxnet virus that the US and Israeli governments used (in 2010) to try to sabotage Iran's nuclear programme - that's also in the series - exploited four zero-days. And if you find a zero-day in new software from Apple, you can really earn big money from it. HackerOne also includes a guy who was previously convicted and now has already made a million through the platform there."

We knew of such a hacker 'defection' long ago in the Netherlands. In 2001, the Anna Kournikova virus -so called because your computer got infected as soon as you clicked on the image of the Russian tennis starlet sent in an e-mail- a million computers worldwide. When 18-year-old Jan de Wit from Sneek was finally unmasked by the FBI, the city's mayor promptly offered him a job.

He had created the virus in a few hours, the young hacker told us, using a toolbox he had downloaded from the internet. "It's still like that," says Klis. "For a few euros, you can order a so-called DDoS attack online that makes someone's site inaccessible. You can buy ransomware on the internet. There are ready-made software packages lying around: it's a service industry."

An industry in which the chance of being caught is relatively low. Although it does happen that an offender is found. As in the CoinVault case in 2018. That involved two Dutch boys who had sent ransomware. "It's very anonymous," says Klis. "The perpetrators don't have a face. You also rarely know where in the world the hack came from. That makes prosecution complicated anyway. In 2018, the South Korean Olympics were hacked. There were strong indications that they were Russians, but there were things in the code that made it look like they were North Koreans. Or Chinese. That's an interesting dimension to these spy hacks: it becomes so unclear who did it. Is it Iran? Is it someone pretending to be Iran? Is it a criminal organisation? Is it the government itself?"

In terms of espionage, we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg anyway, Klis thinks. It all sounds not very hopeful, but too gloomy is not necessary, according to him anyway. "For the series, I also spoke to people from Google and Mozilla (known for the web browser Firefox), who say 'we've really woken up now'." In any case, the aim of his podcast is not to scare people, Klis stresses. "But it's not bad to be a bit scared I think. I mainly hope the podcast will make people more aware, and yes, a hell of a bit scared, that too."

BREAKING HACKS

In 1999. Perhaps the first virus that made people realise that computers were not so very safe after all. Put together out of boredom by a programmer from New Jersey (the same one, incidentally, who helped the FBI unmask the Dutch creator of the Anna Kournikova virus). Each infected computer forwarded it to yet another 50. A fifth of all computers in the world were infected.

In 2006, a hacker from China inserted into computers around the world a piece of software that allowed him to control them remotely. In this way, he managed to steal secret information from organisations and companies from more than 14 countries. Defence companies, the UN, WADA (anti-doping organisation), the IOC - they were all victims.

An Iranian programmer managed in 2011 to use fake security certificates (if you visit a site that does not have such a certificate, you immediately get a warning) to make people worldwide think they were logging into Google or Yahoo. It allowed him to look into all sent mail and steal private information.

In the same year 2011, it became clear that a hack could cost a lot of money. A hacker penetrated Play Station's own network. The result: theft of personal data of 77 million users and a disrupted system. Play Station went on lockdown for 20 days and lost an estimated $170 million.

Hackers from a Russian government-affiliated hacker group, at least that is the suspicion, penetrated the computer systems of government agencies and companies around the world in 2020 via automatic updates of the Solarwind (network software) company. Microsoft had to acknowledge that the hackers had even gotten to the holy grail, the source code. Meanwhile, the extent and damage is still not entirely clear, and neither is whether it is completely over...