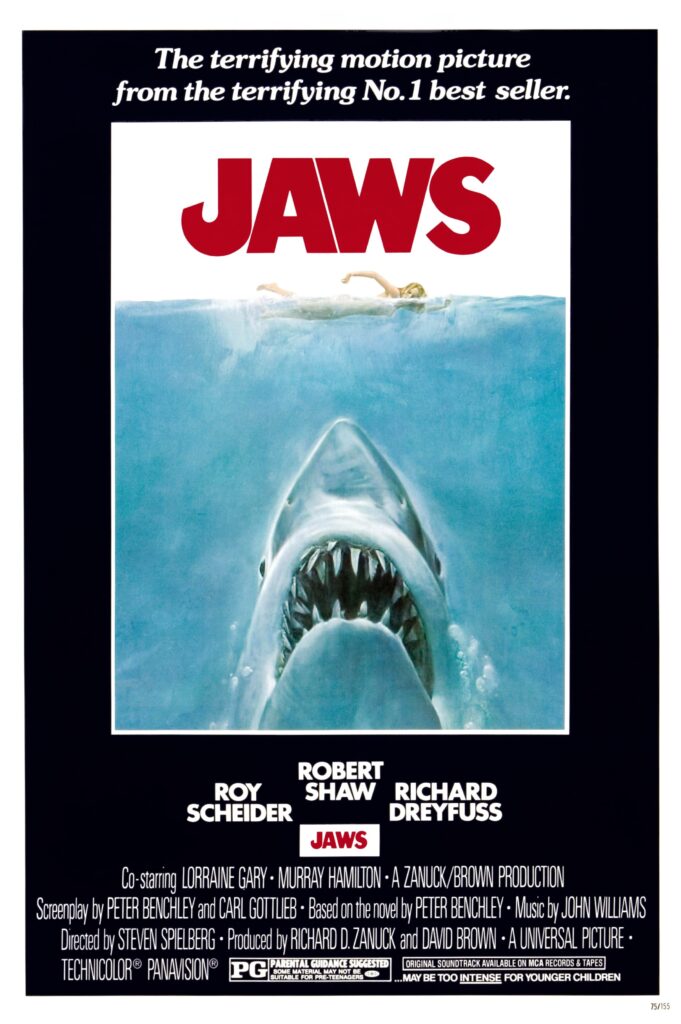

This summer marks exactly 50 years since Jaws premiered. What began as a disastrous production eventually became the first ever blockbuster. Gentlemen's Watch reconstructed the birth of the Hollywood classic with razor-sharp teeth.

Text & interview: Eric le Duc Photography: Universal Pictures, HBO Max, Guido Leurs, Elias Levy via Flickr

...Amity Island, the summer of 1975. As night falls, Chrissie and Tom break away from a group of partying youngsters in the dunes. Touched and excited, they run to the shoreline. She wants to swimming, but he is too drunk to get even one shoe off. While Tom falls asleep in the surf, Chrissie swims graceful laps. Then: a tug on her leg. And another. The woman disappears underwater and surfaces, coughing. She screams out in pain and fear. Again she is grabbed, shaken violently and thrown against a buoy. "Oh, my god", the swimmer mumbles after which she is pulled down again, never to surface....

Behold the opening scene of Jaws, the chilling thriller about a bloodthirsty white shark terrorising the waters around a picturesque coastal town. Next June marks exactly 50 years since the adventure became an instant monster hit, literally and figuratively. A spectacle too that ensured that beaches remained empty and no one dared to dip even a toe in the sea or ocean. But initially, it did not look at all like Jaws would become the classic it is today. For the film began as a doom-and-gloom production full of insecurities, setbacks and crackling arguments.

It is 1973 as Cosmopolitan-chief editor Helen Brown stumbles upon Jaws: The Summer of the White Shark, a book by author Peter Benchley. She tips the novel to her husband David, a producer at Universal Pictures who in turn alerts colleague Richard D. Zanuck to the adventure. After reading the book, the studio executives gleam with excitement: there's a movie in here! For $150,000, they buy the rights to the novel and for a sum of $25,000, Peter Benchley gets to write the script. For the direction, filmmaker Dick Richards is approached. But when he keeps talking about a 'whale' during the first storyboard meeting, he is kindly but firmly shown the door.

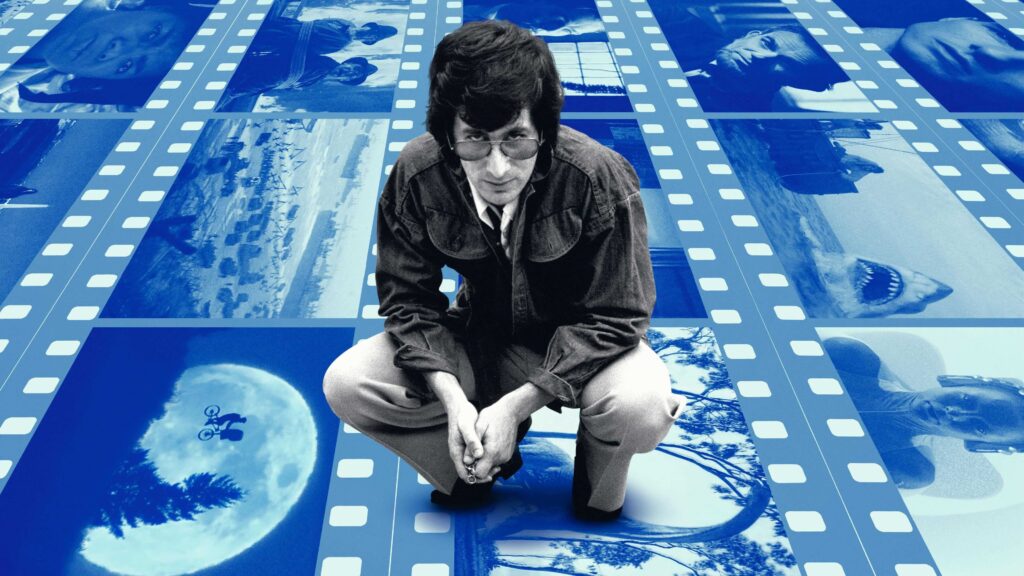

Then one day one Steven Spielberg sees the script of Jaws lie on the Universal desks. The then 27-year-old directing talent -who has just made his debut with the roadrage thriller Duel- first thinks it's about the history of dentistry. But when he reads that it is a story about a white monster shark, he exclaims: I want to make this film! Zanuck and Brown look at each other and take the gamble. Spielberg himself will later say, "I was young, overconfident and stupid. I had to and would make this film. But a basking shark jumping onto the back deck of a fishing boat and devouring a human being, how on earth was I supposed to portray that?"

A production plan is drawn up, after which filming should start on 2 May 1974. But nine days before the first day of filming on and around Martha's Vinyard, Massachusetts, there are three problems. The script is not ready, no actors have been committed yet, and the biggest stumbling block: how should the shark be portrayed? Then Peter Benchley and cinematographers Howard Sackler and Carl Gottlieb manage to get the script finished just in time. And after dropping out of big names like Lee Marvin, Dustin Hoffman and Charlton Heston, Roy Scheider (as police chief Brody), Richard Dreyfuss (oceanographer Hooper) and Robert Shaw (shark hunter Quint) are contracted.

A solution is also found for the shark. An initial plan to train a real white shark soon turns out to be mission impossible. A combination solution is chosen. Shark experts and documentary makers Ron and Valerie Taylor will shoot footage of real white sharks in South Australia. In Hollywood, production designer Joe Alves and effects specialist Robert Mattey will be tasked with creating an animatronic: a mechanical shark that does what director Steven Spielberg wants. With moving jaws, neck, gills and tail, the eight-metre-long fake beast becomes a feat. Spielberg purrs with satisfaction and names his toy Bruce, after his own 'sharky' lawyer Bruce M. Ramer.

The production that can then still begin is disastrous. Filming at sea proves especially challenging. Bad weather, strong currents and strong winds make cast and crew violently seasick. Even the trawler that serves as Quint's fishing boat Orca almost sinks. "Save the actors!" shouts Spielberg through his megaphone. "Fuck the actors, save the very expensive equipment!" screams back sound engineer John Carter. Back on shore, Peter Benchley suddenly starts to morph. Initially, the book writer and screenwriter gets another guest role as a TV reporter reporting on the shark attacks. But when he says he totally disagrees with the utterly ridiculous denouement Spielberg has come up with, Benchley is immediately fired by the director.

Meanwhile, the tension between the star actors is also palpable. Robert Shaw appears to have an alcohol problem and is almost constantly under the influence. "Sober, Shaw was a real gentleman," Roy Scheider will later say. "But after one drink he turned into an incredibly competitive bastard." One day, Richard Dreyfuss is so fed up with his colleague's drinking that he snatches his glass and throws it overboard. Shaw is seething and continues to harass Dreyfuss for the rest of the shoot. He calls him a sissy and sprays him full in the face with a fire hose. For Dreyfuss, the measure is then. "Fuck you, I won't work with you anymore!" he roars. The argument between the actors turns out to be golden for the love-hate relationship Hooper and Quint have in the film. Dreyfuss: "After shooting, we made up for everything. But Robert Shaw was the biggest ego I have ever encountered."

To make matters worse, Bruce appears to be malfunctioning. The fake shark -of which three versions were made- was tested in fresh water. But the sea around Martha's Vinyard is salty, which affects the electronics. On the very first day, the animatronic worth $250,000 sinks, after which numerous repairs and modifications are needed. Spielberg also thinks his Bruce is not scary enough after all and, frustrated, renames him 'the big white turd'. All setbacks necessitate a solution that ultimately turns out to be a boon for the film. Spielberg decides to show only parts of the shark with suggestive shots of a shadow and a fin, then later in the editing and with the ominous music of John Williams, he manages to push the tension to the boiling point.

The planned shooting period of 55 days will become one of 159 days. Due to time and budget overruns, Spielberg fears resignation. But then -on 6 October 1974- the final scene is completed. The people of Martha's Vinyard breathe a sigh of relief. The islanders -some of whom were paid $65 a day to play screaming beach guests- are more than fed up with Circus Spielberg. By way of adieu, the crew members want to throw their director into the sea after the last take. But Steven gets wind of the plan and immediately after Bruce goes airborne with a thunderous explosion, a boat and a car take him straight to the airport. At home in Los Angeles, the months of stress result in panic attacks and nightmares. In them, the traumatised director dreams that the film flops after which he floats lonely and alone on the ocean.

But... the film does not flop. When Spielberg secretly attends a test screening in Dallas, after a gory scene, he sees a man running out of the auditorium and vomiting in the lobby. A good sign, the director thinks. Confirmation that he has gold in his hands follows on 20 June 1975: the day of the premiere. Spielberg drives past New York's Rivoli, one of the 490 cinemas where Jaws will run for the first time. He sees queues well around the corner and laughs, "What lucky bastard made this film?" Jaws is a sensation, spending 14 weeks at number one and being the first film to gross more than $100 million. This makes the monster hit the first blockbuster ever. The film also wins three Oscars: for best music, editing and sound. Steven Spielberg would later say: "Jaws is a fun film to watch, but was a terrible film to make. But I owe everything to it." And Bruce? Who is enjoying a well-deserved retirement at the Oscar Museum in Los Angeles.

To the sharks

After the success of the book and film, Peter Benchley and Steven Spielberg subsequently regretted the way they had portrayed the shark. The misrepresentation of 'killing machine' and 'maneater', was called by Jaws sparked a frenzy among sport fishermen to catch as many great white sharks as possible.

"Deplorable," thinks Guido Leurs (33), marine ecologist and shark expert at the University of Wageningen. "I was 14 or 15 when I Jaws saw for the first time. On television, with my father. Despite being young, I could of course see that the shark was fake. Still, I found it a fascinating film that incredibly captured my imagination. But Jaws did indeed not do the shark's reputation any good. After the film's premiere, shark hunting intensified. In some tourist spots, they are still actively caught away because swimmers are afraid of them. They think sharks are monsters, but in reality they are fantastic animals. They are now found in areas where millions of people also use water. Then 10 deadly attacks a year really aren't much.

"Deplorable," thinks Guido Leurs (33), marine ecologist and shark expert at the University of Wageningen. "I was 14 or 15 when I Jaws saw for the first time. On television, with my father. Despite being young, I could of course see that the shark was fake. Still, I found it a fascinating film that incredibly captured my imagination. But Jaws did indeed not do the shark's reputation any good. After the film's premiere, shark hunting intensified. In some tourist spots, they are still actively caught away because swimmers are afraid of them. They think sharks are monsters, but in reality they are fantastic animals. They are now found in areas where millions of people also use water. Then 10 deadly attacks a year really aren't much.

Funny really that we don't accept that. If I'm jogging on a savannah and I get attacked by a lion, I'm the dummy. But if a surfer gets bitten, it is always the shark's fault. But a shark will never deliberately attack a human being. He may well think we are prey. And because they have no hands, they take a test bite first. And yes, it can be deadly.

Currently, 30% of all shark and ray species are threatened with extinction. Due to overfishing, loss of habitat... This is bad, because sharks are important for ecosystems.

Currently, 30% of all shark and ray species are threatened with extinction. Due to overfishing, loss of habitat... This is bad, because sharks are important for ecosystems.

How can we improve the reputation and population of sharks? Watch documentaries, read about them, go to presentations. And: know where the fish you eat comes from, because bycatch of sharks and rays in fish and shrimp fisheries is a big problem.

Of course his Deep Blue Sea and The Meg genius but also wrong films. In them, sharks are depicted as mythical maneaters, just to scare the viewer. In reality, there is no need for that. Despite being predators, you can basically have a safe interaction with sharks. As long as you respect them."

On the occasion of the 50ste birthday of Jaws National Geographic made the documentary Jaws@50. This can be seen on National Geographic.