Gentlemen's Watch tried to snare him for some time, in vain. And then suddenly, on a sunny day in March, there's email: "Ha Hans, Let's Talk, Greetings! Ad."

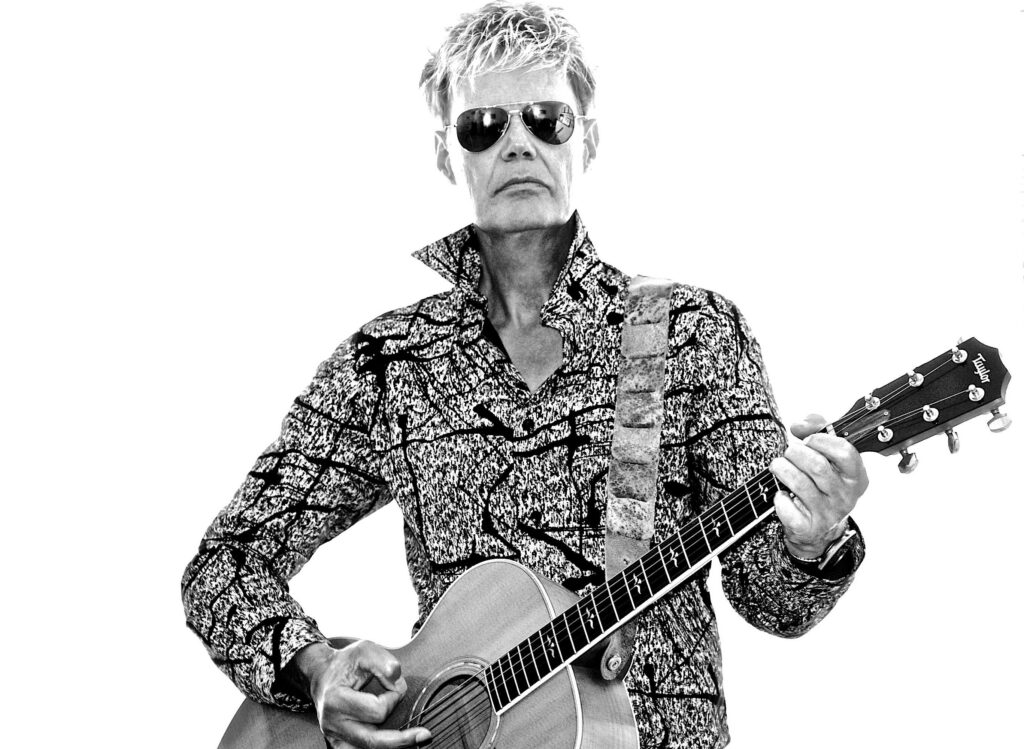

Text & photography: Hans van Wetering

When is convenient, I ask when I call him the day after. Next week? The week after? "Come now," he sounds decided, "the sun is shining, and every day is different, everything is constantly changing, look at Trump." A generous smile. I still flounder a bit, preparing the interview a bit, that would be handy anyway. But Visser is determined. Ok, what time then? End of the afternoon? "No ya, the sun is shining now, come now!"

He gives incredibly detailed directions -there by that white farmhouse on the left, then a small house on the right, with remarkable white facade, then into that little street by... you'll see... and there you go... and then you get to....- and an hour later we're sitting on a terrace in the centre of Laren. His terrace, as Visser lives nearby, everyone knows him here. During the interview, he is constantly greeted by passers-by.

"You do have to mention the name of the terrace," Visser says as we sit down: "The Lex, we're at the Lex! Nice people, just started, hence. Anyway, beauty so, let's start, we'll see where we end up."

"That particularity of that life you're thrown into -such as: sort it out, sort it out with your shit..."

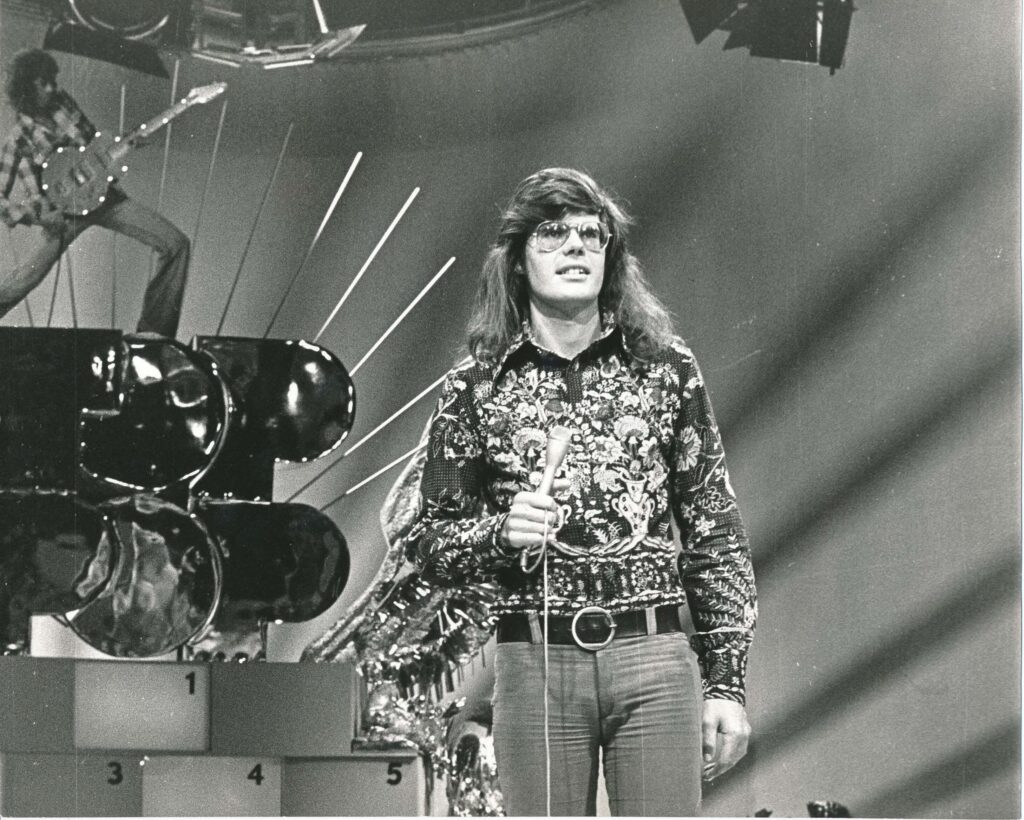

Most people know Ad Visser (Amsterdam, 28 April 1947) of Toppop, the iconic pop programme broadcast by AVRO between 1970 and 1985. But that is only part of the story. Visser not only made countless radio and TV programmes, he also wrote books, made theatre (with intriguing titles like 'Hitec-heroes' and 'De tirade van de dolle hond') and art performances (for instance, he transformed a Boeing 747 into a musical instrument).

Label manager of the prominent record label Island Records for record company Universal, he was as well. And oh yes, also studied marketing, "because nobody did that in the music industry at the time, seemed convenient." That came in handy when he walked into the AVRO building as a young boy ("I went to the AVRO, because I thought it was a beautiful building. I first walked past all the buildings, the VPRO had some little villas, didn't seem like anything, and the TROS building that was really terrible, a sick building") and walked in there unannounced to the director of programmes to pitch a radio programme, the Superclean Dreammachine: "There would music would be heard that could not be heard on Dutch radio, I said. And that surely it suited AVRO exactly to offer broad repertoire, a programme for young people! Big abroad already! This is going to be huge! Not long after, they called: go and make it. That was in 1968, that's when it all started."

Visser grew up in posh Amsterdam Zuid. His father was a grain merchant, his mother painted, designed hats. A culture-loving family, in which he was taken to the municipal museum at an early age ("The exhibition Bewogen Bewegen, in 1961, with Pol Bury and Jean-Pierre Tinguely: I loved it. From there the ship departed...") at a very young age was given all the freedom to go his own way. Literally, too.

Asked about his first experience of beauty, Visser starts talking about the route he took as a little boy from home to school, that he avoided some streets because he found the buildings ugly, that he detoured via the concert hall. Visser mentions street after street after street, as if he were walking the route again at that moment, seeing the buildings and the streets again.

Why one building is beautiful and another terrible, why one song grabs you by the throat and another doesn't, you mustn't analyse it too much, Visser says: "because then you start converting that process into language, you turn it into definitions. And perception and word usage, there are kilometres between them, miles, light years! As soon as you start naming it, you disrupt that special process."

Visser did all kinds of things, but he sees himself primarily as a singer-songwriter. During his time of fame as a radio and TV producer, he made pop music, partly under the radar, and that was deliberate. He had seen enough misery, Visser says, musicians ground down by the industry, perishing on the wild side. He had national and international success in the early 1980s with his multi-media project Sobrietas, a futurological novel with accompanying soundtrack. Had a top 5 hit in Italy. He experienced it himself: "Then I thought: my god, I must make sure I never have big success, then I'll go to shit, because I like this lol. When I scored a gold record, which happened several times, I immediately let go of the project."

Yet another passer-by greets Visser, a sip of coffee, silence. Then suddenly: "When I hear myself talk like that... I talk about myself as a success story. You have to dose that, otherwise they say: hasn't he experienced any goddamn shit at all? What a bastard! I never need to hear from him again." Laughter.

"Afterwards we said to each other: yes, if it had ended there, what a fantastic ending that would have been!"

He kept making music all these years, but not according to the formats demanded on the radio. Not seeking success, but keeping the music pure, Visser says. That was what he was all about. Following your intuition and then seeing where you end up. An avant-garde pop band, Blurpp, that's where it started, in the 1960s. "We were going to perform on TV one day. I had written a song with the lyrics 'Iek, Iek I'm a freak, and I get a kick out of a bottle of prick'. That was stopped by the broadcasting board the same day." Visser laughs: "The argument was: this must be about narcotics." He has since made more than 40 albums, some 28 of them as a solo artist.

Visser is a talker, constantly stringing together anecdotes. "I digress," he says after the umpteenth digression, "so your story goes to shit. Because I still have some things to tell." He grabs his phone, looks for something. It turns out to be a list he made during the time writer dezes was sitting unprepared in the car on the way to this terrace. (Reads) "No, you don't have to..." (Reading continues) "Oh yes, that yes... whether you do anything with it doesn't matter, but I have to have told you, otherwise it won't be any good."

How he met his wife, that needs to be told. Because that too is a story of beauty; a story in which the legendary guitar amp VOX AC30 - the amp used by the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, among others - plays a starring role. Nobody had one like it. And Visser was unexpectedly able to try one out during a last-minute scheduled gig. "Maximum volume of course! Wonderful! So nice! So beautiful!" Wife Melanie was in the audience. 57 years they have been together now.

"The beauty of connection," he says a little later. "When we visit a city together, we go our separate ways. I have very long legs, she short, it doesn't work. We would always meet at a certain point then. But at one point, if we were in a city we had never been to before, we said: we won't agree on anything, and see where we end up. And the fascinating thing is: we always bump into each other. Those routes eventually come together. Yes, that's beauty. It goes beyond any logic. Apparently, we have developed a special radar together. That's the beauty, the depth of that connection, that you can be so sensorially connected."

Routes, tracks, paths; the words keep recurring during the interview. The route from home to school, the route along the broadcasting buildings, the routes Visser and his wife walk separately, the route from Amsterdam city centre to this terrace in Laren. Routes you often choose without knowing exactly why, tracks and paths you end up on "if you keep all the windows of your perception open all the time". Routes that keep branching off without you having a conscious grip on them, as this conversation itself turns out to be such a fanning out route, "like life itself," Visser says.

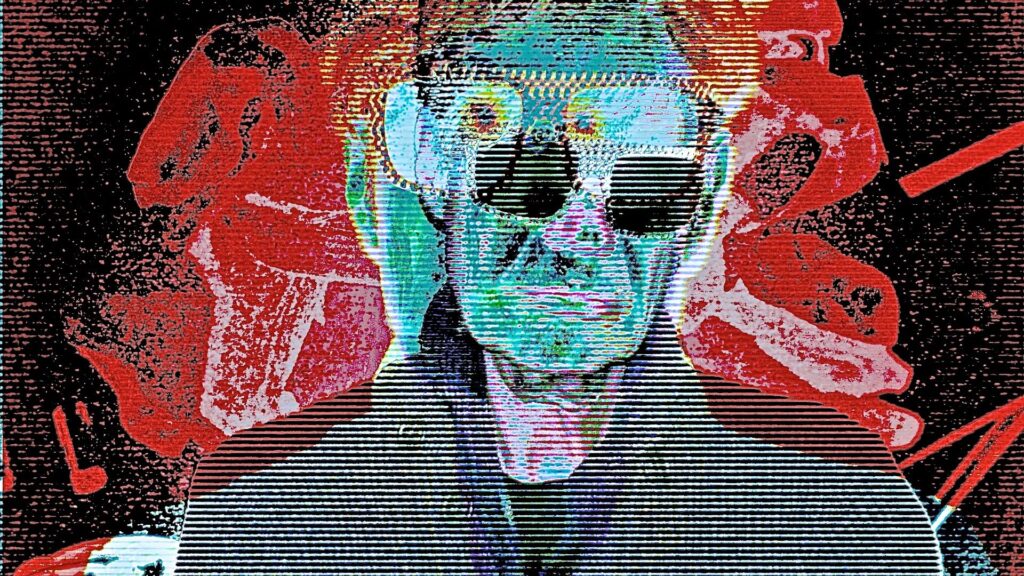

It comes to his project The Parade of Heavenly Tragedy. Of all the things Visser did, this is perhaps the most bizarre. It is an 8-hour-and-39-minute song. The longest song ever written. And as with many other things he made, it wasn't meant to be, Visser says: "I didn't use a standard, I followed the path the song indicated. Of course, I could have said: sixteen verses, that's good for radio. But I don't care about that. I'm on an adventure. The song leads me to where I need to come out. The engine of that process is: trust. I let it go and so more and more verses were added. At one point I thought: this will never end, this will go on until I die. And I accept that. But then, after 1050 verses, it got quiet, it was done. I had a song with a beginning, a middle and an end."

The music industry responded scornfully; the art world saw it differently. Visser was approached by the Groninger Museum. The song became a performance, was acquired by the museum; the only pop song in the world in a museum collection.

"What the song is about? About the muddling and fumbling of man, always trying to get a grip on existence and discover the essence of life. The beauty of mysticism, that's really it. That peculiarity of that life you're thrown into -such as: sort it out, figure it out with your mess- and that there are so many layers; that you think it's happening in your head, but that in the meantime it's also elsewhere, that you think you have a nice idea, but that it was actually already there so to speak, in all kinds of forms, all playing along: that mysticism, that's beautiful."

An elderly lady with gold-rimmed butterfly sunglasses, snow-white hair and an if possible even whiter poodle greets warmly ("All right, Adje?"), the waitress comes by again to ask if everything is to his liking (Visser again: "The Lex huh! The Lex!"). He still talks about his latest project, a record made with the Metropole orchestra, titled Ruthless: Casanova, Gainsbourg and Dali ("a mission to hack their brains") and then it's time to take photos, including a selfie for the wife of writer dezes: because Ad Visser was a hero, she grew up with Toppop. "Me too," Visser says. "It's no different for me, I went through the same journey."

He looks again at his list of stories he wanted to tell. "Well, it's already more than enough like this. But I will say what you are missing now. I still wanted to tell you about the beauty of nature, about absolute silence. And what you are also missing: the beauty of fate. In Greece, Melanie and I got on a yacht and ended up in a terrible storm. Waves of seven to 12 metres. That was so beautiful! Occasionally the sun would come through there, through those foaming waves! I was lying on the deck and those waves were crashing on me, it hurt! And cold, cold, never been so cold in my life. We were very close to each other, but couldn't talk to each other, so loud was the storm roaring. Afterwards we said to each other: yes, if it had ended there, what a fantastic ending that would have been!"