In addition to photographic works of prehistoric dinosaur skeletons, the German art photographer Christian Voigt (b. 1961) gained international acclaim for his monumental, hyper-realistic landscapes and architectural photography. The adventures of astronauts exploring the limits of human horizons were the starting point for his new series LUNAR. "Earth is our only spaceship." A conversation with a technical subject fanatic.

Text: Kirstin Hanssen Photography: Christian Voigt

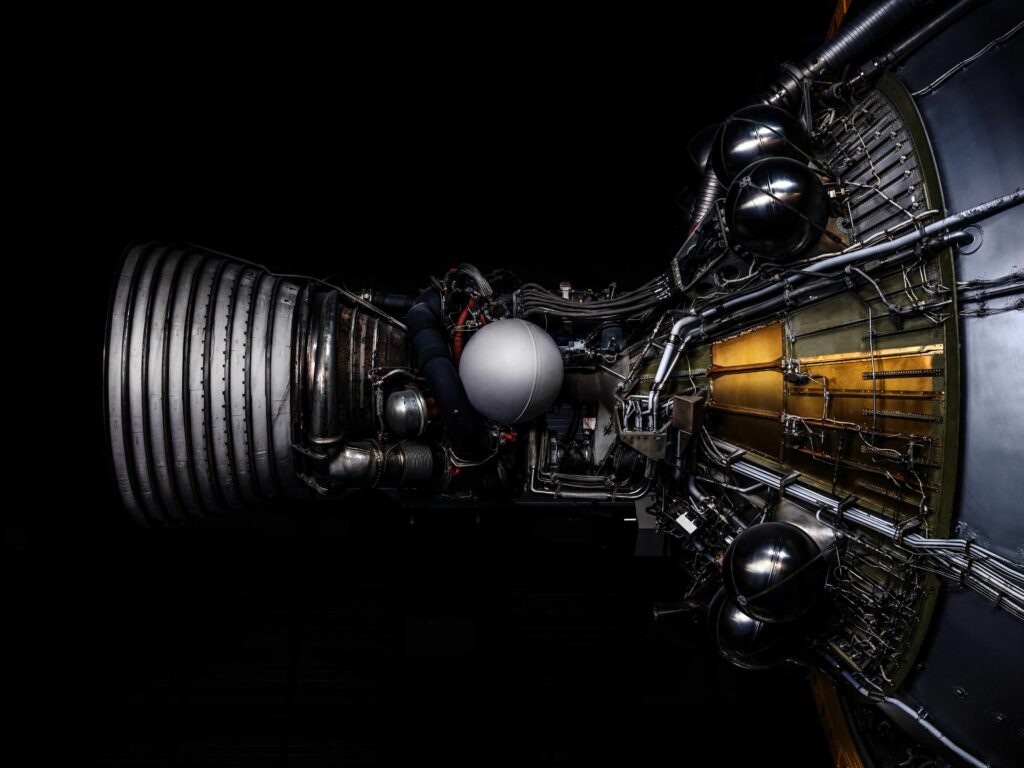

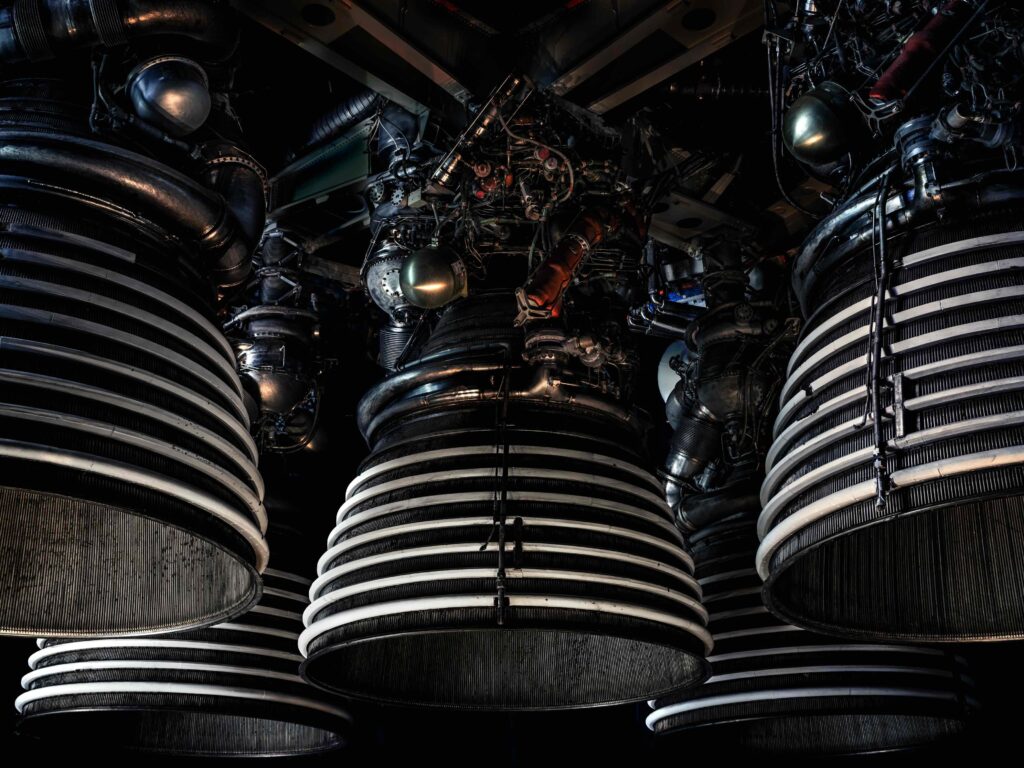

Christian Voigt opened a new exhibition at Amsterdam's 2024 at the end of October Wanrooij Gallery, where his latest work LUNAR was exhibited in large format. "For the frames, we came up with something special with Martijn Wanrooij so that they match the prints extra well," Voigt says. The works show iconic spacesuits and technological marvels from the US and Russia in a unique way, against a black background. From the bulky suits of the early years to the modern, sleek suits of today, the images show the constant evolution of space technology see. What stands out in his work, and has now become his signature, is Voigt's photographic realism with razor-sharp, richly detailed photographs. This is the result of what he describes as "the perfect blend" between his analogue Swiss camera and a digital post-production.

Christian Voigt opened a new exhibition at Amsterdam's 2024 at the end of October Wanrooij Gallery, where his latest work LUNAR was exhibited in large format. "For the frames, we came up with something special with Martijn Wanrooij so that they match the prints extra well," Voigt says. The works show iconic spacesuits and technological marvels from the US and Russia in a unique way, against a black background. From the bulky suits of the early years to the modern, sleek suits of today, the images show the constant evolution of space technology see. What stands out in his work, and has now become his signature, is Voigt's photographic realism with razor-sharp, richly detailed photographs. This is the result of what he describes as "the perfect blend" between his analogue Swiss camera and a digital post-production.

To the moon and back

Since childhood, Voigt has been fascinated by space travel. Around the 50th anniversary of the moon landing in 1969, he started working on the LUNAR project. "The moon landing is in the spotlight again now that NASA is preparing the Artemis mission. Fifty years ago, it was only the US and Russia that carried out lunar missions. It involved countless tests before Neil Armstrong took his first step on the moon. I wanted to capture the original spacesuits and objects from the 1960s and 1970s as a visual ode to that analogue space age, as I call it," Voigt says.

The project had almost limited itself to US objects, but in 2019 he made a significant trip to Moscow. An organisational feat, because with a camera you need numerous permits. "We were lucky: our return flight was the last one before the Covid lockdown. Now I wouldn't be able to go to Russia for this work."

The project had almost limited itself to US objects, but in 2019 he made a significant trip to Moscow. An organisational feat, because with a camera you need numerous permits. "We were lucky: our return flight was the last one before the Covid lockdown. Now I wouldn't be able to go to Russia for this work."

Baikonur Cosmodrome as a dream

Then the pandemic delayed the project for about two years. He then travelled to the US, where NASA proved very helpful. "NASA also allowed me to photograph objects that normally remain behind closed doors," he says. Sometimes Voigt plays with reality, as with the helmet of the Apollo 17 suit reflecting the lunar mobile. "We used an existing photograph to spark the viewer's imagination," he says. Although the series is now complete, Voigt has one more dream: access to the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, the world's largest rocket launch base, run by the Russians . "As an outsider, and especially as a photographer, it is extremely difficult to get permission to enter the site, let alone take professional photos at this heavily secured location. But it remains a great desire. Perhaps LUNAR will get a sequel one day."

Peace among the stars

Peace among the stars

Voigt reflects on cooperation between nations in space: "It's amazing what people can achieve when they work together, like building a rocket. If you look at old pictures, you can see how they made the calculations with the earth's gravity. Of course, there were computers back then, but many of those calculations are still just worked out on paper. And what I have also observed: during space missions, war does not exist. There, Americans and Russians work side by side, flying together in capsules to space stations. Maybe they talk politics over lunch, but in the end everything is about teamwork, not nationalities."

Earth as mother ship

Voigt is fascinated by the unstoppable human urge to leave our planet and discover new worlds. "However, it remains twofold. On the one hand, it costs billions to organise these space voyages, while children are still dying of hunger. Did you know that there is more knowledge about the universe than about our oceans? We can fly to the moon, but we can't manage to keep our rivers clean. And I don't want to come across as a fanatical environmentalist, but I sometimes wonder: are we really made for space travel? Isn't the earth actually our spacecraft and our bodies a spacesuit, so to speak? It is important that we do not destroy the Earth, because she is our only spaceship."

Incredible or implausible?

Incredible or implausible?

Voigt continues philosophically: "We understand what a black hole is, but what is behind it is not yet fully understood. Perhaps we will never fully grasp the idea of space. I always say: 'We can fly to the moon, but the rest is fantasy.'"

Building on that, some people don't believe the moon landing actually took place. As we look at the spacesuits and equipment Voigt has captured so brilliantly, it seems incredible that people shot through space with them. "Let's make it clear at the outset that I am absolutely not questioning the moon landing," Voigt stresses. "In fact, I talked about it during a personal meeting with Buzz Aldrin, the second man on the moon.

He explained that the experience was completely different for him and Neil Armstrong than for the masses. People have no idea what it was like to be shot to the moon in such a cramped cabin and walk around there. That's beyond comprehension. But that doesn't mean that's why it never happened. When Aldrin was later asked about this by a reporter, he gave the man a big slap in the face in response."

Sustainable photography

Sustainable photography

Speaking next about the lightning-fast development of AI and the image overload via social media, Voigt says: "In 20 years, we will have to add that these are real photographs. I want to make authentic images that last; images you want to look at more often and in which you can discover something new again and again. Images that are not 'swipeable' but invite you to dwell on them, like you might do with a painting in a museum. That is what I hope to achieve with my exhibitions: that people leave with images in their heads and think back to my work."