"I think there is a lot of ugliness in the world. That irritates me. If you take the train through to the Netherlands, it's pitiful sometimes, all those industrial sites full of soulless buildings. I then think: how can you want to put up such ugly things?"

Text: Hans van Wetering Photography: Hans van Wetering

Marc Oosterhout is a brand strategist. The 'brand doctor' of the Netherlands, as he is sometimes called, was one of the founders of advertising agency N=5. He advised numerous multinationals, wrote several books on brand strategy and regularly sat in on talk shows to talk about his profession; to talk also about the role of brand strategy in politics, about his meddling with the PvdA and Lodewijk Asscher.

We find ourselves in the kitchen of Oosterhout's residential farmhouse, located in the floodplains of the river Lek, in the Betuwe. From the kitchen, we look out over the estate. Twenty years ago, he and his family came here from Bussum in search of space, in search of nature, far away from those industrial estates, from that careless ugliness.

We find ourselves in the kitchen of Oosterhout's residential farmhouse, located in the floodplains of the river Lek, in the Betuwe. From the kitchen, we look out over the estate. Twenty years ago, he and his family came here from Bussum in search of space, in search of nature, far away from those industrial estates, from that careless ugliness.

"It's five hectares," says Oosterhout, "which is quite a lot. When we came here, we knew nothing about gardening. We wanted to make it neat, as it is now, but we soon found out that that was impractical."

They delved into 'natural management', into 'rewilding projects'. The idea: create something with minimal intervention and then leave it to nature itself. "Then we discovered what happens when you let nature take its course a bit, the huge beauty which then arises naturally." He points: "There in the distance, we planted a food forest, now it has to support itself, with a very little help from us." And laughing: "You have to be able to stand weeds, of course, or it won't be anything."

You have to let nature take its course a bit, but that is not the same as letting God's water flow over God's field. There is a vision behind it, Oosterhout says, a vision of nature and landscape that is reflected in all aspects of the estate's management and design. "When we talk about beauty; that's not just in the experience of that nature, the beauty is also in that vision, in the whole."

You have to let nature take its course a bit, but that is not the same as letting God's water flow over God's field. There is a vision behind it, Oosterhout says, a vision of nature and landscape that is reflected in all aspects of the estate's management and design. "When we talk about beauty; that's not just in the experience of that nature, the beauty is also in that vision, in the whole."

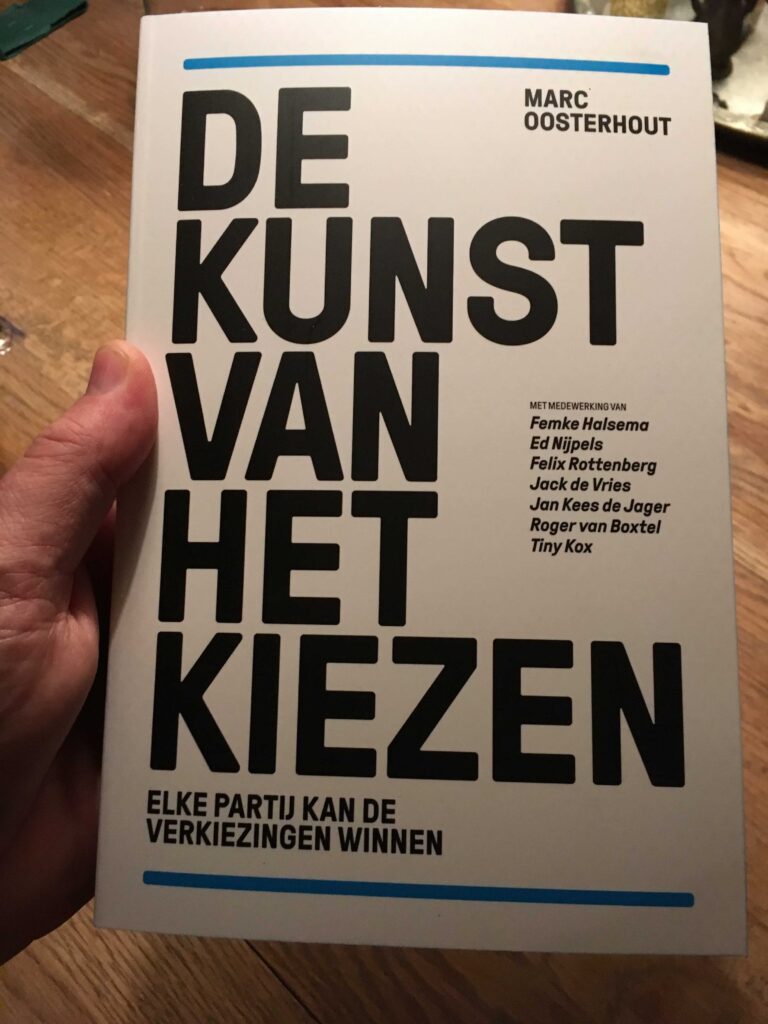

Oosterhout walks to the window, as if to verify something, then returns and sits down. On the table is a stack of books he wrote himself. The art of choosing on the role of marketing in politics ("got a lot of attention, but hardly sold"), a booklet on women's football ("my daughter went to football, I knew nothing about it, stood along that line, thought: while I'm here, I might as well write something about it"), books on brand strategy.

"Beauty lurks everywhere," Oosterhout says as he sits down again, "and in my work it's really no different. It's there at all stages of a project. It starts with the first idea, with developing a thought, a vision; the moment you know it's right. It's in the imagination of that idea, in advertising films. It's also in that one line that ties the message together."

He talks about a project for the Reading Coalition, an association of schools, libraries, the literary museum and the Reading Foundation funded by OC&W: a campaign to get people reading again. "For that, together with the advertising agency, we came up with a theme line: 'Who reads, has a story'. Frits Spits compared it in his programme De Taalstaat to Heerlijk Helder Heineken, said it was that level. 'Who reads, has a story': that phrase really hits the mark, in it everything comes together, the is right. That too is beauty, it makes me very happy."

Another one of those phrases, Coolblue: 'Everything for a smile'. Oosterhout: "That's a really nice moment when you've found that. That little phrase answers the question: Who are we really?" And a little later: "That's actually what I do, that's my job: finding out why you are there as an organisation: what is the ultimate message?"

Another one of those phrases, Coolblue: 'Everything for a smile'. Oosterhout: "That's a really nice moment when you've found that. That little phrase answers the question: Who are we really?" And a little later: "That's actually what I do, that's my job: finding out why you are there as an organisation: what is the ultimate message?"

Other names come along; organisations and companies he is currently helping to rediscover who they are, and, that too, of course, advising how to bring that rediscovered identity into the world. "A good example is..." But no, rather not mention that one, and, a moment later: "No, not this one either." People need to get out, it's socially sensitive.

Finding out why you are there, that is the beginning, the essence. But the outcome must then be marketed, through such a catchy phrase, that is, and through images: advertising posters and films.

In doing so, authenticity is paramount, Oosterhout says. "Real beauty comes from the content. Something can be beautifully designed, super aesthetic, but if it doesn't touch people, it's nothing. That kind of empty beauty usually has to disguise the fact that the creators didn't get out of it."

He laughs: "Not that this is to say that you can make ugly things. I'm in the world of seduction art after all, I want to draw people into a story."

We walk outside. Arrive at a wooden building. "We had this put up in 2016. It has been featured in all kinds of international magazines. It's basically a shed containing work and living space. A few years ago, a guy from Boston was suddenly in front of us, making a book on barn houses, insisted on having this in it. It was built to blend in with its surroundings, Oosterhout says, "it's part of a vision, it's right, and yes, so that's beauty too."

Inside the barn, we enter an orangery-like space. In a side aisle, a sheep scurries around ("we'll keep it inside for a while, a wolf has been spotted"). At the far end of the orangery, sandwiched between planters and garden equipment, is a gorgeous, creamy-white Mini ("one of the last ones made, my son helped refurbish it").

Inside the barn, we enter an orangery-like space. In a side aisle, a sheep scurries around ("we'll keep it inside for a while, a wolf has been spotted"). At the far end of the orangery, sandwiched between planters and garden equipment, is a gorgeous, creamy-white Mini ("one of the last ones made, my son helped refurbish it").

No, his meddling with the PvdA did not help, Oosterhout says. "But if Lodewijk had not stepped down because of that allowances affair, the PvdA would have been a much bigger party now, I am convinced. We had spent three years campaigning on subsistence security. However, that was abandoned after Lodewijk's departure. Now it is at the forefront of every party. Actually, we were ahead of our time. But yes, you can have such a great strategy, if your leader is flaked out then it's done."

Not every brand is salvageable, in short. Oosterhout interfered with the VPRO programme Backlight, which was announced shortly before this interview that it will disappear. He once visited Blokker for an introduction and advised them that there were opportunities if the company reinvented itself as "the household help of the Netherlands". That meant not only a range concentrated on washing machines, irons, washing powder and everything else associated with housekeeping, but also that Blokker should come to represent expertise in that area, such as: if you have a very difficult stain in your jumper, then go to Blokker. "But they chose the slogan 'Blokker has it all'. Blokker has everything, that was the message. But that's exactly what you shouldn't do, because everything is nothing."

It comes down to US politics and, inevitably, Donald Trump: "That America first, he started that in 2016, and he has kept it up ever since, endlessly. I don't agree with Trump's narrative at all, but he is running a hugely effective brand strategy. It's a clear story, whatever else you may think about it. Trump knows what the people want: he presents himself as the strong leader, as the shrewd businessman who won't let himself be taken for a ride, as the man who will make sure that ordinary people, who are suffering from inflation, will have more to spend. And then Harris starts talking about freedom, about the value of democracy. It's all hindsight, of course, but that message was far too complicated."

Figuring out why you are there as an organisation, what the ultimate message is, that is his job. And, the follow-up, how to bring that 'brand' to people's attention. And that brand, that could be anything, a supermarket chain, a TV programme, a political party, even a church: the Protestant Church Netherlands asked Oosterhout to help it 'sharpen' the church's story: "The question was: 'what are you there for as a church?' We came up with the word 'soul happiness', which is what many people are looking for these days."

Everything is a brand, it comes down to that, and everything has to be marketed.

"Whether it is an airline, an NGO, or a political party; the question you should always ask yourself, which should guide your relationship with the outside world, is: where do I differ from the others, why should people choose me and not another?"

You have to know who you are, and then you have to seduce people. Yes, Oosterhout says, that often means emphasising things that make life beautiful, fun and exciting. But that doesn't mean you can create a reality that doesn't exist. "Marketing lies, it is regularly said. Yes, that may have been true in the past, but today it is totally unacceptable. The time when we could sell our stuff unrestrained is over. People demand much more from companies and organisations anyway. Social responsibility, for instance. That's why I work with more and more brands on their social positioning. People often think that advertising people are cynics, who will do anything to sell the worst crap, but that's really bullshit. That's what I discovered when I started: most people working in marketing are idealists; those creatives are often left-wing types, not interested in money."

You have to know who you are, and then you have to seduce people. Yes, Oosterhout says, that often means emphasising things that make life beautiful, fun and exciting. But that doesn't mean you can create a reality that doesn't exist. "Marketing lies, it is regularly said. Yes, that may have been true in the past, but today it is totally unacceptable. The time when we could sell our stuff unrestrained is over. People demand much more from companies and organisations anyway. Social responsibility, for instance. That's why I work with more and more brands on their social positioning. People often think that advertising people are cynics, who will do anything to sell the worst crap, but that's really bullshit. That's what I discovered when I started: most people working in marketing are idealists; those creatives are often left-wing types, not interested in money."

We are outside again, looking out over the estate. "Look," says Oosterhout, "that's the food forest, and over there, those trees over there, those are walnuts: we have so many that we now supply local restaurants, as a hobby mind you."

He drops a silence, then says: "In Bussum, we had a street lamp in front of our house. Here it is really dark. At first we found that scary, it is perfectly quiet and pitch-black here, but now I can enjoy it intensely. Sitting here at night, staring into that nothingness, the world completely absent... Yes, that really is the most beautiful thing there is."