"When you sat in the Reynolds stand at Ajax, in a low spot, you could hear those studs really pounding hard into that grass when he pulled up and started sprinting. I'll never forget that. That was a kind of explosion, because he was skinny, scrawny, but with enormous power. If you experience that at such close quarters, that's really incredible. Cruijff was graceful, yes, but it's never about his enormous power. At Cruijff you had strength, agility and speed at the same time."

Text: Hans van Wetering Photography: Frank Ruiter (portrait), Hans van Wetering

Amsterdam, a cold January day. In his flat on Zeeburgereiland, TV-maker-journalist-writer Henk Spaan prepares a cappuccino. He is in town for a while, Spaan says, the flat is in fact a pied-à-terre. "Usually we are in France, at least there I can work through: no worries, no book presentations, no restaurants," he says. He laughs, "and no friends."

Seventy-four is Spaan now, but sitting still is not one of them. He writes a daily column for The Parool, is working on his fifth novel, based on the rehabilitation process he went through after he fell two years ago and, after two operations, had to learn to walk again. And then there is his editor-in-chief of Hard Grass, the literary football magazine he founded with Matthijs van Nieuwkerk in 1994.

"Until then, Dutch literature never dealt with football," says Spaan. "That was too little. Until 1990, you don't come across the name Cruijff once in Dutch literature. But in countries like America, Brazil and England, it was perfectly normal for writers to write about sports in novels."

"Until then, Dutch literature never dealt with football," says Spaan. "That was too little. Until 1990, you don't come across the name Cruijff once in Dutch literature. But in countries like America, Brazil and England, it was perfectly normal for writers to write about sports in novels."

He mentions Portnoy's Complaint Of Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud's The Natural, in which baseball plays an important role. And did I Fever Pitch read, by Nick Hornby? "Wonderful book, which isn't really about what happens on the pitch at all. He writes about the peripheral stuff, about how everyone is always grumpy in stadiums, for example, and that he looked up anxiously at the men around him who were always swearing so much."

These are experiences he recognises, says Spaan: "As a child I also found the stadium scary, all those big guys. And especially when you had to piss, in one of those long iron troughs along the wall, I found that really repulsive. You could see those guys' cocks. And that stench too, that smell of piss everywhere."

Those early football memories are etched in Spaan's memory: the first time in the stands, along with his father, who played football at the village club. "On Saturday afternoons he would hang up the nets and draw the lines, with one of those iron carts with a hole at the bottom where the lime came out. That was really magical. And on Sunday, I watched breathlessly as he bandaged his legs at home." Everything was enchanting, says Spaan, those strange attributes, those weird studs under those kicks, his first football boots ("An uncle's old shoes, with steel toecaps in which I had to put newspaper stuffs, otherwise they were too big"), his first 'leather marble' ("I was about ten years old, I really slept with that, it smelt so terribly good").

Those early football memories are etched in Spaan's memory: the first time in the stands, along with his father, who played football at the village club. "On Saturday afternoons he would hang up the nets and draw the lines, with one of those iron carts with a hole at the bottom where the lime came out. That was really magical. And on Sunday, I watched breathlessly as he bandaged his legs at home." Everything was enchanting, says Spaan, those strange attributes, those weird studs under those kicks, his first football boots ("An uncle's old shoes, with steel toecaps in which I had to put newspaper stuffs, otherwise they were too big"), his first 'leather marble' ("I was about ten years old, I really slept with that, it smelt so terribly good").

"Is he going again, that madman. No Yuki!"

The cat that has been quietly scurrying around all this time suddenly jumps onto the kitchen counter.

Spaan laughs.

"No, not allowed, get off."

But Yuki clearly has no appetite for that.

"He looks for water, while there are water bowls all over the house. He used to drink from the tap, and now he thinks: here somewhere it must be, but where... Almost 21 years old he is, dementia probably."

Chip puts the cat on the ground, sits back down knowing.

"And the smell of grass too, the smell of that freshly cut grass."

Spaan played football himself, once playing a trial match at Amsterdam's DWS, in those years one of the top clubs in the Netherlands, but was not picked out, unlike his friend. "However, I was allowed to come back the following week. Another chance, I thought, but then it turned out it was to act as a sparring partner for the lucky ones who did get selected. I was reasonably quick, and I scored, but I was also stiff, not a great talent."

Spaan played football himself, once playing a trial match at Amsterdam's DWS, in those years one of the top clubs in the Netherlands, but was not picked out, unlike his friend. "However, I was allowed to come back the following week. Another chance, I thought, but then it turned out it was to act as a sparring partner for the lucky ones who did get selected. I was reasonably quick, and I scored, but I was also stiff, not a great talent."

You were not a player you would like to watch yourself now?

"Are you besotted, no."

Beautiful footballers, then you talk about Cruijff, about George Best, says Spaan, about Rensenbrink and Bergkamp. He mentions Ziyech and Nouri, about whom he wrote a book. "And Van Persie of course, he really was the prototype of a beautiful footballer: elegant, a bit stiff too, but because he had so much ball control, you don't notice that anymore."

Technique has to be efficient, says Spaan. "For me, beauty in sport is always linked to results." Players who lose themselves in chops and feints he does not like to watch. Anthony, the frivolous Ajax attacker who now plays at Manchester United: Spaan doesn't like it. Ajax legend Tscheu La Ling, who threw out his 'scissor move' on occasion and was chanted by fans (all balls to Tscheu!): Spaan should have little of it. A scissor move is fine, but only if it produces something. Like Piet Keizer, who passed his man with scissors during the 1971 European Cup final against Panathinaikos, allowing Dick van Dijk to score. At least, that is how that famous passing move went down in the football annals. In reality, it was not scissors at all, says Spaan, as Keizer once confided to him: "I just went a little to the left and then I crossed him."

Technique has to be efficient, says Spaan. "For me, beauty in sport is always linked to results." Players who lose themselves in chops and feints he does not like to watch. Anthony, the frivolous Ajax attacker who now plays at Manchester United: Spaan doesn't like it. Ajax legend Tscheu La Ling, who threw out his 'scissor move' on occasion and was chanted by fans (all balls to Tscheu!): Spaan should have little of it. A scissor move is fine, but only if it produces something. Like Piet Keizer, who passed his man with scissors during the 1971 European Cup final against Panathinaikos, allowing Dick van Dijk to score. At least, that is how that famous passing move went down in the football annals. In reality, it was not scissors at all, says Spaan, as Keizer once confided to him: "I just went a little to the left and then I crossed him."

Scissors or not, it was one of those goals that is forever burned into your retina.

"Did you see that goal by Rashford against Arsenal this weekend?" asks Spaan suddenly. "Rashford gets the ball, in the approach he passes his direct opponent, who is really nailed to the ground, and a tenth of a second later he shoots that ball from twenty metres into the far corner. That is real beauty, there is not an inch of superfluity in that. You really have to watch it back!"

The best goals ever?

Impossible task, says Spaan, there is so much. Bergkamp, the goal against Argentina and, even better, the one against Newcastle United in 2002: "I watched that four times last week. An unfathomable goal, you really have to watch it very often to understand what is happening; it can not at all."

There is a goal from Van Persie too, Spaan says after some thought.

The diving header against Spain?

'No, no, another one, a cross from Clasie... Jesus, when was that again?'

He grabs his phone. A moment later: "Ha, this is him, the Dutch team against Ecuador, May 2014. A tight pass, from the centre spot almost, Van Persie catching the ball on the chest and ramming it into the net in one go with his left. He practised endlessly on that too, didn't he."

Spaan breathes a sigh... "There are so many beautiful goals. And when you are gone I think: I should have mentioned that goal, and that one..."

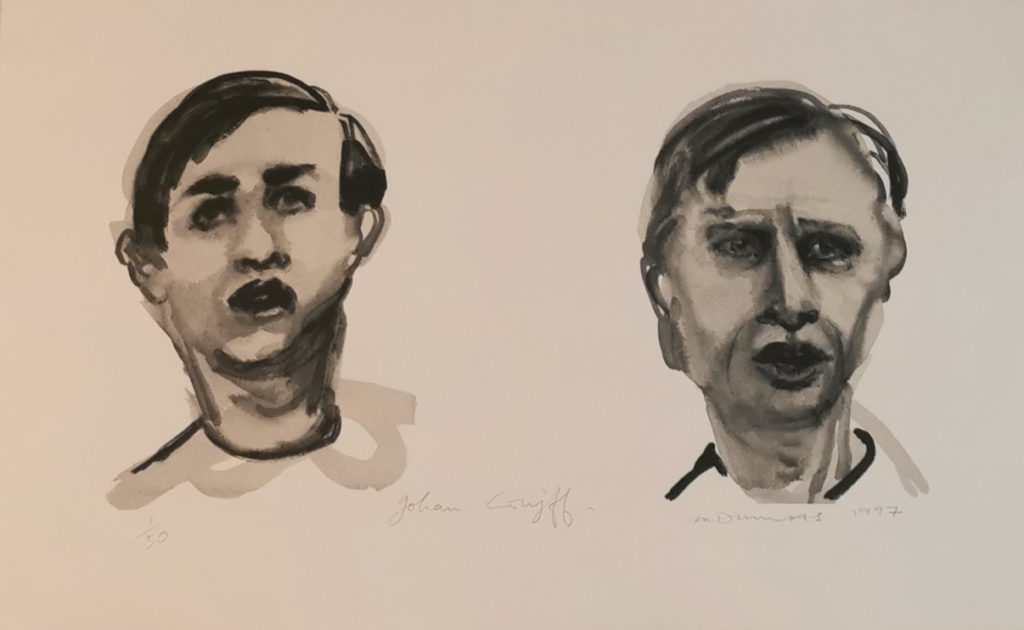

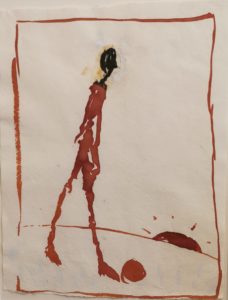

We walk to his study. On the wall a lot of Cruijff. A Giacometti-like drawing by artist Toon Verhoef, of a solitary figure with a ball on his foot (Spaan: "Every top athlete is lonely in what he does, because no one is as good as he is"), a screen print of a young and an adult Cruijff by Marlene Dumas, a painting by Emo Verkerk in which the footballer looks almost panicked ("Cruijff was always scared, had fear of failure. Almost never took a penalty huh, says enough").

We walk to his study. On the wall a lot of Cruijff. A Giacometti-like drawing by artist Toon Verhoef, of a solitary figure with a ball on his foot (Spaan: "Every top athlete is lonely in what he does, because no one is as good as he is"), a screen print of a young and an adult Cruijff by Marlene Dumas, a painting by Emo Verkerk in which the footballer looks almost panicked ("Cruijff was always scared, had fear of failure. Almost never took a penalty huh, says enough").

On an adjacent wall two paintings of the Arena under construction. The artist, Arie Schipper, drove to the stadium every morning for two years and painted the progress. "What's beautiful about it? The anticipation, I think, of what it will become. Now that I look at it this way, I realise...it's almost the same emotion as when you wake up on a match day, when you have to play football yourself: that feeling of anticipation, I remember from the old days, that was great! And the crushing disappointment afterwards when the match was cancelled. What did you have to do then! Your day collapsed, no, your life collapsed."

A number of footballers are briefly reviewed. About Frenkie de Jong ("With him, you always have the idea that he actually has something better to do. Ninety per cent passion and commitment, but the other ten per cent is elsewhere, I think in Arkel or so"), about Ronaldo ("That's not even football! You give a deep ball, he goes running and he shoots it in, well"), about Mbappé ("A very beautiful footballer. I don't like to make comparisons with game, but he really runs like a cheetah").

Then the interview is done.

The physiotherapist waits, "maybe some more writing."

The question of what beauty is, how one might define the term, has gone unanswered. Spaan does not yield.

"There are hundreds of conceivable expressions of beauty, otherwise unrelated. A landscape description by Couperus, a gear by Cruyff, the sight of a stadium under construction: beauty is endless."

But when someone says something is beautiful, you know what they mean, right? Surely there is then a shared experience?

However, Spaan does not allow himself to be caught. Beauty is all kinds of things, putting that diversity under one heading is rubbish. No philosophising, please.

In the corridor by the front door hangs a plastic grass tile, work by Arnhem artist Henk Peeters.

In the corridor by the front door hangs a plastic grass tile, work by Arnhem artist Henk Peeters.

"I was about eight years old when I first went to the stadium with my father. I remember well that I was just shocked at how green the pitch was. Jesus, so green! That that's possible! Just like seeing the sea for the first time. The Olympic Stadium, the second ring still on it. That was one of those experiences you never forget. If you ask me what beauty is... that first time that grass under the bright light of those stadium lights, yes, that was really magical."